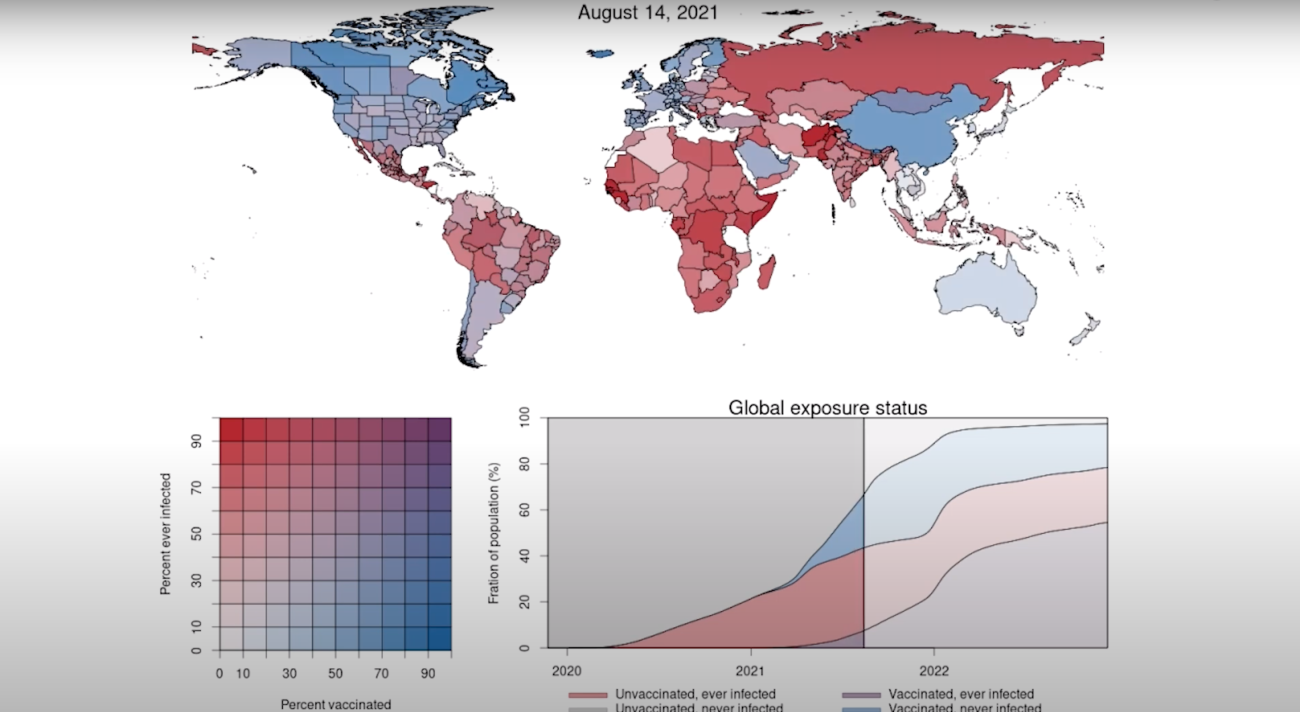

The COVID-19 pandemic has followed a complex, horrific, and erratic trajectory over the past three years. Recent work from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) looks at where this winding path has taken us and where we are heading next. Using computer simulations to understand the global impact of COVID-19, the new study shows that although the deadliest phases of the pandemic are likely behind us—thanks to widespread immunity—the world should remain vigilant and prepared for a variety of future scenarios that could unfold as the pandemic enters its fourth year.

The First Three Years

Robert Reiner and his colleagues at IHME used advanced modeling techniques to capture the course of the pandemic from December 2019 through June 2023, estimating the number of daily infections, hospitalizations, and deaths for all locations in the world. This research charts the twists and turns that the pandemic has followed and illustrates how new variants have shaped its evolution.

SARS-CoV-2 was first detected in late 2019. By March 2020, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. The original form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus predominated during the first phase of the pandemic. By September 2020, new variants of the virus began to spread, including alpha, beta, and gamma. Those variants were responsible for the majority of infections through the end of 2020 and into 2021.

During the omicron outbreak, more than 98 percent of SARS-CoV-2 infections were due to omicron

The delta variant emerged in late 2020 and spread globally, sending the pandemic in a dire new direction. During this outbreak, the number of global daily deaths skyrocketed, eclipsing pre-delta rates. This dramatic increase in deaths was due to delta’s exceptionally lethal nature — infections associated with this variant resulted in more severe disease than any previous variant.

In late 2021, the omicron variant emerged, altering the course of the pandemic once again. Omicron was more infectious than other variants. As a result, the number of global daily infections reached an all-time high during the omicron wave, infection rates dwarfing the peaks associated with previous outbreaks. Fortunately, omicron lacked the high disease severity associated with delta. Despite the vast number of omicron infections, deaths were proportionally far fewer relative to other variants. During the omicron outbreak, more than 98 percent of SARS-CoV-2 infections were due to omicron; however, nearly 25 percent of COVID-19 deaths during this period were attributable to delta. Approximately three million people died worldwide from COVID-19 during the omicron outbreak, roughly the same number of deaths globally each year due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (the third leading cause of death worldwide in 2019).

Paradoxically, the transmission of omicron has provided much of the world with immunity through infection. IHME scientists estimated that as of mid-December 2022, more than 97 percent of people worldwide had some level of immunity against SARS-CoV-2, derived from either past infection or vaccination, or a combination of the two. This level of immunity could help move the world away from pandemic and epidemic levels of transmission toward an endemic COVID-19 hovering at a baseline level.

Future of the Pandemic

It is likely that new variants will continue to influence the trajectory of COVID-19. It is almost impossible, however, to predict the characteristics of a new variant prior to its arrival, making forecasting a complex and challenging task.

Given this ambiguity, the researchers designed five variant scenarios that could unfold during the coming months. The pictures in these scenarios were diverse, ranging from a situation in which no new variants emerge to a devastating circumstance in which delta-like severity is combined with omicron-like infectiousness in a new variant, deltacron. In all but the worst-case scenarios, the forecast global death rate was relatively low due to the high level of global immunity that has resulted from previous and ongoing omicron waves and vaccination efforts.

The greatest loss of life occurred in the deltacron scenario. This scenario envisions the worst possible variant displaying exceptionally high levels of contagiousness and disease intensity and having the ability to overcome one’s immune system. The chances of this type of variant evolving in the real world are low.

The work of Reiner and his colleagues illustrates how new SARS-CoV-2 variants have repeatedly changed the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moving forward, people should anticipate a range of potential variants to prepare for a future that is unknown and difficult to predict. Luckily, this study demonstrates that the vast majority of the global population possesses some level of immunity to SARS-CoV-2, suggesting that the worst days of the pandemic may be behind us.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the COVID-19 research described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual authors and are not necessarily shared by their institution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The authors would like to thank Rebecca Sirull for fact-checking the piece and Katherine Leach-Kemon for providing feedback.