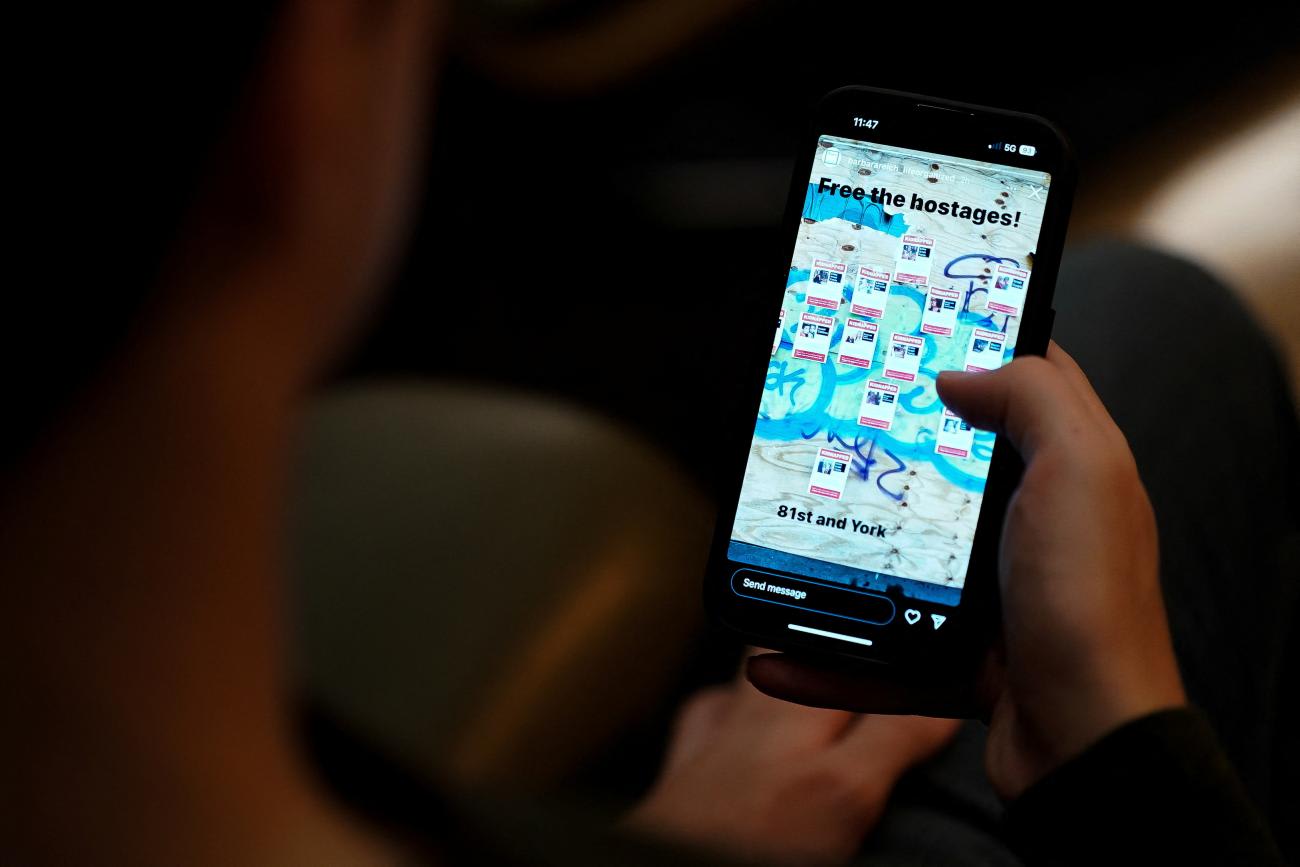

After Hamas launched its attack on Israel on October 7, news and social media channels were flooded with images of the gruesome conflict. Those photos, often depicting injuries, sexual violence, and destruction, are considered critical to illustrate the severity of the war but also contribute to the trauma that viewers at the scene and from afar experience. A catastrophe that affects an entire society—referred to as collective trauma—increases the risk of mental distress.

The more people view images of violence, the greater the likelihood they will experience psychological distress. In some cases, people may develop more serious mental health conditions such as secondary trauma (the effects of indirect exposure to trauma) or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Typical symptoms of PTSD include intrusive thoughts such as upsetting unwanted thoughts or images, sleep disturbances, and physical signs such as nausea or aches. Any observer can experience a range of human responses to these events, but getting stuck in negative emotions raises cause for concern, explains Alicja Podgorski, a trauma therapist at Dr. Laidlaw & Associates in Ontario, Canada, who specializes in treating first responders.

The more people view images of violence, the greater the likelihood they will experience psychological distress

"The media becomes a conduit through which collective trauma is spread," says Dr. Alison Holman, researcher at University of California, Irvine, who studies the mental health implications of traumatic events, including the attacks on 9/11, the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, and the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando in 2016. Similarly, the Israel-Hamas war is a collective trauma.

In 2013, Holman conducted a study investigating the impacts of the Boston Marathon bombing and found that viewing six hours or more of footage of the scene per day was associated with higher acute stress than being at the finish line in Boston that day. The worry, fear, and uncertainty induced by a collective trauma can lead people to seek information about it in the media, which spurs greater worry and fear and leads to even more trauma-related media exposure, ultimately creating a cycle of distress.

People who share an identity with victims of a traumatic event are also at an increased risk of distress. In the aftermath of the Pulse nightclub massacre, which targeted LGBTQ+ and Hispanic individuals, a recent study by Holman found that people who shared those identities reported greater acute stress than those who did not.

The Israel-Hamas war naturally intersects with and emotionally affects individuals with religious or ethnic ties to the region. When media reports show the killing of children and videos of women being sexually assaulted, parents, survivors of sexual violence, and others who identify with the victims are at risk of experiencing heightened distress.

What's Happening in Our Brains?

When people perceive a threat, their bodies go into fight-or-flight mode, when the amygdala—a primitive part of the brain that is responsible for the perception of danger—takes control. This normal, short-lived response to danger prepares people to react to the threat.

"For some, they who have a personal stake in this [war], a relative in Israel or Gaza, and this news is highly emotional and invokes a threat. But even to those who don't have those connections, it's still . . . a new real threat that could destabilize our world," says Dr. Steve Joordens, a psychologist and professor at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

Prolonged activation of the fight-or-flight response creates a state of hyperarousal, meaning that people are constantly on guard, leading them to be more irritable, angry, and tired. The chronic stress evoked from the fight-or-flight response also has long-term implications for mental and physical health. Studies show that chronic stress is linked to developing PTSD or heart disease and can also result in greater incivility in society. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when people worried about themselves or their loved ones becoming ill or dying, reports of violent crime, domestic abuse, and online bullying increased.

Beyond the media coverage, ripple effects of the Israel-Hamas war include a surge in antisemitic and Islamophobic hate crimes that heighten anxiety in both Jewish and Muslim communities. That anxiety compounds with the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic lockdowns, which weakened social connectedness and disrupted mental well-being worldwide, Joordens explains. Now, many people are struggling to activate the parts of their brain that help them express empathy or compassion.

Now, many people are struggling to activate the parts of their brain that help them express empathy or compassion

Bearing Witness Safely

People may feel obligated, or even guilty, if they are not constantly updated or aware of the events happening in Israel and Gaza. Fortunately, there are ways they can attenuate the impacts of bearing witness.

Avoid doom-scrolling, the zombie-like online swiping from one crisis to the next. To minimize the dangers associated with media exposure to collective trauma, people should try to engage with content from trusted sources for no more than thirty minutes a day, Holman suggests. Breaks in media consumption allow the nervous system to rest and recharge, disrupting the fight-or-flight response.

Engage in activities that bring joy and social connection. "Globally, we are all connecting to a lot of feelings of grief and despair right now, and we need to remember what it's like to feel hope and joy," Podgorski says. She and Joordens encourage people to plan and partake in activities that bring them happiness and connection with others, including team sports, dancing, or sharing a meal. Although it might feel strange to match those activities with suffering, doing so can lower cortisol and cause positive hormones to flow, serving as an antidote for stressors.

Take direct action in response to the Israel-Hamas war. For some people, making a charitable donation, protesting, or signing a petition are opportunities for engagement. Others may find solace in communal prayer at local mosques, churches, or synagogues. Many communities have also organized healing circles, offering space for community members to share their experiences and express their feelings.

Report hate. People may also feel empowered by reporting incidents, including online hate, through hate crime apps like the ones developed by B'nai Brith and the Council of Agencies Serving South Asians. Alternatively, people can take steps through organizations such as the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs or the National Council of Canadian Muslims to gain awareness so they can address antisemitism and Islamophobia as they see it unfold.

Learn how to combat discrimination. Right to Be, a nonprofit aimed at ending harassment in all its forms, has been offering free bystander intervention training to combat antisemitism and Islamophobia. Demand for training sessions has increased sharply since the war broke out, with hundreds attending each session — up from the typical eighty-person audience. The one-hour sessions are a starting point toward dialogue and further action.

"I think, for your own sanity and well-being, you want to be able to contribute something positive and something peaceful into . . . this conversation," says Emily May, president and cofounder of Right to Be. "The power in this is being able to hold true to the fact that, yes, the world is on fire, and also you have the power to be a firefighter in your own right."