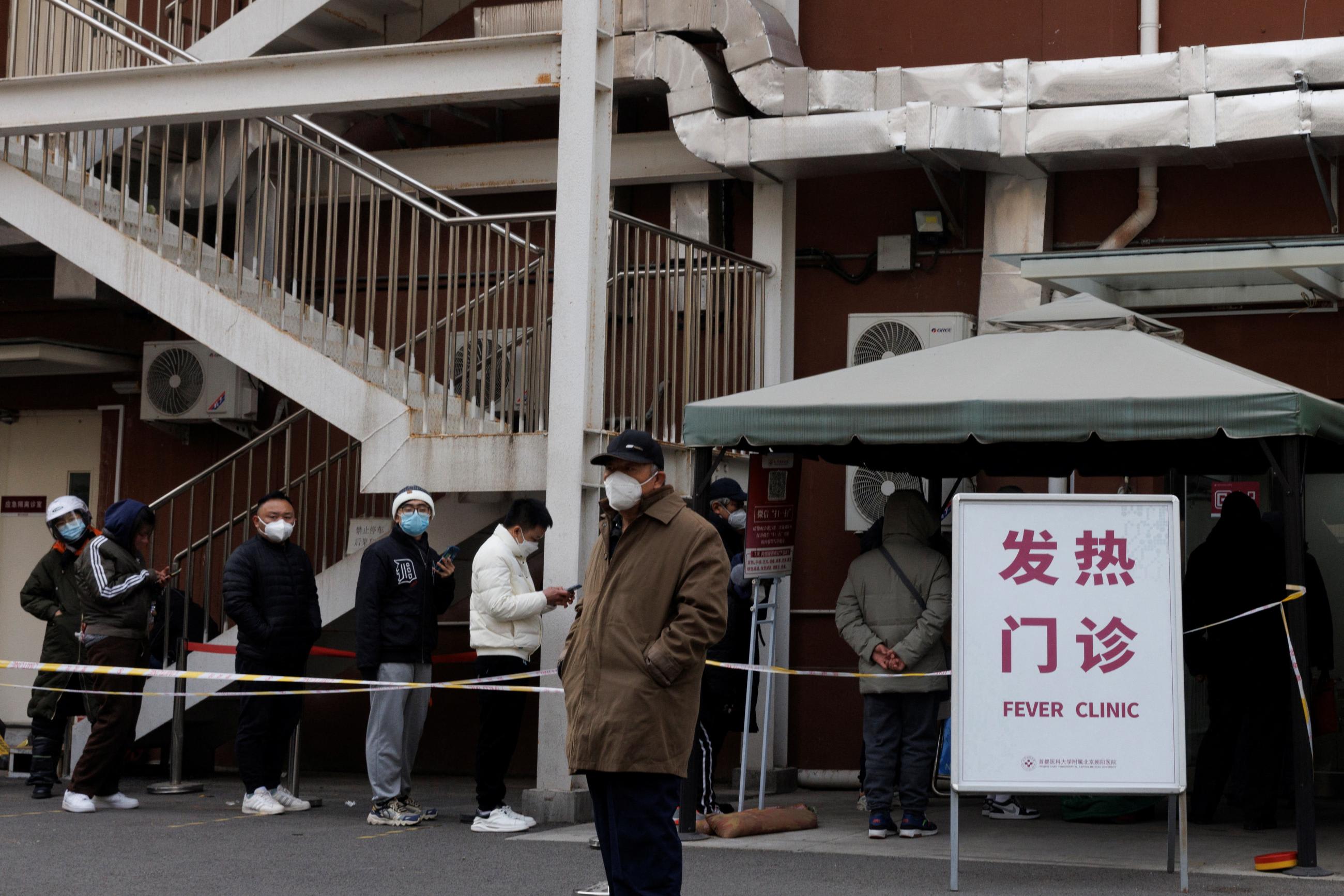

Over the past three years in Beijing, it was rare that anyone knew someone who had caught COVID-19 domestically. In recent weeks, however, after the government scrapped its zero-COVID restrictions, reports are emerging of omicron-linked COVID infections straining resources in China.

Speaking with residents in Bejing now, it seems like everyone knows someone with COVID-19, or they have it themselves. While official COVID-19 figures in China have decreased since December 2, a slowdown in testing and an increase in patients recovering at home means that the actual number of cases is far higher than the official counts.

China has opened 47,000 fever clinics in hospitals across the country in response. Since the 2003 SARS outbreak in southern China, temporary fever clinics have been utilized for epidemics to prevent cross-infection of diseases with other hospital departments. Fever clinics are "a separate unit of an emergency department that specializes in the screening of infectious diseases."

Shenglan Tang, deputy director of Duke Global Health Institute and co-director for Global Health at Duke Kunshan University in China, has researched health and disease control in China for over thirty years.

"From my perspective, [China's] limited resources should be going toward building intensive care units (ICUs) and adding ICU beds," Tang said.

Even with a very low rate of severe cases, omicron's rapid spread in a country of 1.4 billion people means that many in China will soon need ICU beds.

A Fudan University study from late 2020 utilized data from the "2015 Third Nationwide ICU Census"—China's most recent ICU census—to forecast the 2021 ICU capacity for different regions around the country. It showed disparities in ICU bed availabilities, with many less developed provinces like Jilin, Guangxi, and Tibet seeing less than half the rate of ICU beds than more developed regions like Zhejiang, Beijing, and Shanghai.

Overall, the study concluded that "the number of comprehensive ICU beds per 100,000 residents in China is 4.37." In comparison, U.S. ICU bed capacity in 2018 was 27 per 100,000 people—over six times China's 2021 estimate.

Estimating China ICU Bed Capacities

Data projected for 2021

Data on hospital bed availability in 2021 from the National Bureau of Statistics showed that nearly every province, except Guangdong and Chongqing, had significantly fewer beds per 10,000 people in rural regions. For the twenty-eight provinces in China, urban areas had an average of 25 percent more beds per 10,000 residents than rural areas. Nearly 40 percent of Chinese people reside in rural areas. In comparison, the U.S. rural residents makes up less than 20 percent of the total population.

Bed Disparities in Urban-Rural Health Clinics in China

Tang believes that building ICU capacity to handle the wave of people infected with the omicron variant in China should be focused on the central and western regions of China, where the capacity of quality health-care provision is low. Along with distributing mRNA vaccines to the elderly, adding ICU beds where they're desperately needed—especially outside of cities like Beijing and Shanghai—could decrease unnecessary deaths.

"Building the ICU beds in China will not be a waste," he said. "Unlike the construction of quarantine centers, they may not be useful after the waves pass, as we saw with the quarantine centers built for SARS [in 2003]. This way you're investing in the health infrastructure that can also be used for other severe patients, such as stroke patients."

On Sunday, China's National Health Commission released a statement requiring county-level hospitals to upgrade their ICUs and "increase the number of ICU beds to no less than 4 percent of total beds by the end of this month."

After almost three years of zero-COVID policies, it's unclear if these ICU and vaccine measures are coming too late to prevent an onslaught of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality across the country.