In the new book Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19 (HarperCollins 2021), Alina Chan and co-author Matt Ridley assemble and assess the evidence on the major hypotheses for the origin of COVID-19. Chan, a medical genetics researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Ridley, a science writer (author of Genome and The Red Queen), look at the possibility that COVID-19 was circulating in an animal species bought and sold in markets in China and then crossed over to a human during the handling of those animals. It also explores "the lab leak hypothesis" which is based on the idea that scientific research happening in a lab in Wuhan, China, on bat coronaviruses—in an effort to mitigate a future outbreak—caused a global pandemic after an accident involving an exposed lab worker.

Viral surveys a complex assortment of molecular and epidemiological evidence as well as the motivations and actions of some individuals amidst the backdrop of the pandemic. It tells the story of some of the unexpected participants in the investigation into COVID-19's origins—people who sometimes had no prior expertise in biology but nonetheless identified leads that were ultimately substantiated.

Chan recently discussed her motivations for writing Viral, her take on the origins debate, and her hopes for the book.

Think Global Health: How did you and Matt Ridley decide to collaborate on this book together? And did you step back from your work as a medical genetics and synthetic biology researcher at the Broad Institute to dedicate the time to research and write Viral?

Alina Chan: Matt and I first connected in mid 2020 when he was writing a piece for the Wall Street Journal and had read my preprint. After that we continued to chat about emerging findings related to the origin of COVID-19. By the end of 2020, Matt asked if I would be interested in co-authoring a book on the origin of COVID-19 with him. He thought that I would be a good co-author because I had become a key figure in the search for the origin of COVID-19 and have strong expertise in viruses and genetic engineering. We brought complementary skills and knowledge to the table to write Viral.

At that point, I had already been spending most of my free time looking into this question for several months. I did not step back from my work, which I am very passionate about. Scientists in the Boston area can tell you about our extreme work ethic. We don't cut back on work, we just pile more work onto our plate.

After Matt reached out, it took a few more months of deliberation and communication before we jointly agreed that writing a book together would be a good idea. I had hesitated because of concerns about the book resulting in more public exposure. My decision was ultimately driven by the desire to raise public awareness of this issue and advocate for a credible investigation of the origin of COVID-19. For this to happen, all of the key information about the origin of COVID-19 had to be carefully fact-checked and compiled into a single book that would be made widely accessible and approachable to the public. We made our collaboration public after signing with HarperCollins in May 2021.

It's hard to ask whether COVID originated in a lab without being shouted down or censored as a racist, a conspiracy theorist, or anti-science

Think Global Health: At one point in the book, you describe the media as displaying a "magnificent incuriosity" about the origins of COVID-19. How did so many journalists and even scientists become so complacent?

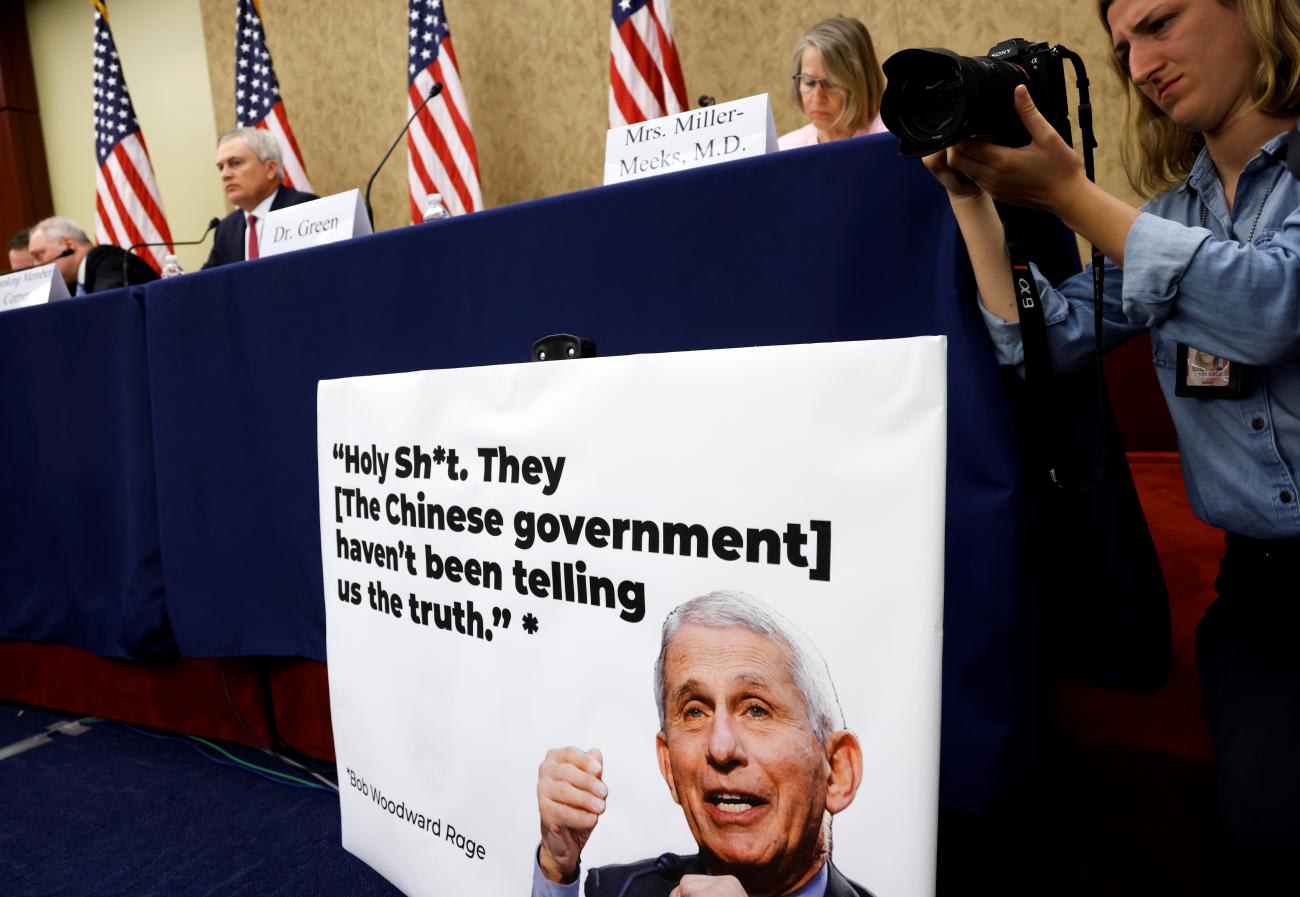

Alina Chan: I think there was a lot of group think happening in early 2020. Once a few prominent scientists said that a lab origin of COVID-19 was a conspiracy theory or not plausible, mostly everyone else, including journalists and major news organizations, fell in line. It became very challenging to ask whether SARS-CoV-2 may have originated from a lab or research activities without being shouted down or censored as a racist, a conspiracy theorist, or anti-science.

Think Global Health: With lockdowns, internet sleuths had time on their hands to investigate the very thing that was giving them the opportunity. In many cases it seems like it was these individuals who made key discoveries. What role do you think these citizen scientists played that more established scientists did not?

Alina Chan: Matt and I describe some of their stories of ingenuity and determination in our book. One of our hopes for the book was to share the achievements of these international citizen scientists—some of whom are real scientists and real journalists—who were doggedly unearthing as many archived websites as possible, news reports, and even academic theses describing the SARS-like virus research that was being conducted in China and elsewhere.

During this process, many of them were condemned as conspiracy theorists, but several of their key discoveries turned out to be true. Scientists were sitting on the fact that when SARS-CoV-2 was detected in Wuhan, nine of its closest relatives were under study in a Wuhan lab; experiments were being conducted that could have plausibly led to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2; and that scientists had planned in early 2018 to insert novel, rare genetic modifications (cleavage sites) into novel SARS-like viruses. Without the work of citizen scientists, I'd say that the public would still be in the dark about many of these findings which are now described in our book.

Think Global Health: Throughout the book I found myself wondering if you and Matt were going to ultimately pick a side—did COVID arise from nature or in a lab. [Spoiler Alert] Personally, I was relieved that you remained agnostic as this saga has been marked by too many people getting beyond the facts. Did you feel any pressure to conclude one way or another?

Alina Chan: I had already been attacked by people on both sides for not choosing a side, even before we decided to co-write the book. People on both sides—natural or lab—have claimed that they're the ones who have the truth and that it is obvious SARS-CoV-2 came from the market or from the lab. It was important for me to make it clear to both scientists and non-scientists that there is currently zero dispositive evidence for either a natural or lab origin of COVID-19. Without dispositive evidence, how can we say which origin scenario is the most certain? A single piece of definitive evidence can instantly upset all of our estimates.

Right now, my hope is that everyone can agree that, regardless of which scenario they personally think is more likely or obvious, what we really need is a credible investigation into both natural and lab origin hypotheses.

Think Global Health: The book makes the case that lab accidents are actually fairly common. Yet, one of the consistent misconceptions regarding the debate on COVID-19's origins seems to be people assuming that the alternative to a natural spillover event is a manufactured bioweapon. In your opinion, have some authors been purposely conflating the lab accident scenario with the bioweapon scenario to try get people to dismiss the possibility of an accident altogether?

Alina Chan: I don't want to speculate on people's motivations unless they have reasonably perceived conflicts of interest. However, I agree that there has been a lack of coverage of how common lab accidents are and how much more frequent they are getting as dozens or hundreds of new pathogen labs are built around the world. There is an urgent need to establish an international moratorium to regulate risky pathogen research – to make these projects more transparent and to minimize the impact of lab releases of pathogens.

I can't judge the scientists in China who had information because they work and live in the context of an exceedingly different culture and government

Think Global Health: In reading your book I found myself feeling like there was fault to go around. Taking one example, premier journals such as The Lancet and Nature seemed to have dropped the ball in fully vetting those early and influential pieces. Do you agree with that assessment? In your opinion, have organizations like these as well as other media organizations looked hard enough at themselves in the mirror?

Alina Chan: I do feel that some of the top journals and news organizations have fallen prey to internal biases about how they think the virus most likely originated or which experts are more likely to be correct or reliable. I have personally experienced and heard of others' experiences with gatekeeping and censorship to suppress articles about a potential lab origin of COVID-19 or even articles just questioning the validity of arguments for a natural origin. There should be a careful review and measures taken to ensure that when future outbreaks occur, we don't fall into the same traps again. There are many things we can do—make peer review open, ensure timely data sharing, incentivize independent verification of publications or data that pertain to epidemiological investigations, and improve systems to identify and declare competing interests.

Think Global Health: For me, a heartbreaking moment in the book is when you write, "Imagine how differently the world would have reacted if, in January 2020, the WIV had announced that the closest relatives of the novel coronavirus came from a place where half of the infected people had died from a mysterious respiratory disease—and that nine closest relatives to SARS-CoV-2 had been under study at the Wuhan Institute of Virology long before the COVID-19 outbreak." Do you find yourself haunted by the harm that could have been averted if people in the know had been more candid at the outset?

Alina Chan: I cannot judge the scientists in China who had this information because they work and live in the context of an exceedingly different culture and government. To this day, I don't believe that they can speak freely about what they know. However, I do find it unacceptable that collaborators outside of China were not forthcoming with key information that could have pointed toward a lab origin of COVID-19. Back in early 2020, there was a lot of confusion about the novel coronavirus—where it had come from and what its capabilities were. Many experts, scientists, and doctors told the public that this was less concerning than the flu, that this was yet another virus spilling over from the wildlife trade. It created a sense of invincibility among some subset of the public—that this was just a rerun of the first SARS outbreak and would be limited to a few thousand patients, largely in Asia. If the experts and public had been informed of what we know today about the SARS-like research occurring before the pandemic and a potential lab origin of the virus, I do believe that the messaging and response would have been completely different.

Think Global Health: You believe "the truth will out" and I hope you are right. However, in the meantime, how do we prevent the next pandemic when there is no consensus on the origins of this one? How do we find the political will to take all of the possible origins of COVID-19 seriously in terms of policy response?

Alina Chan: A July 2021 joint letter to Congress signed by dozens of scientists and science organizations said: "We urge you to reject attempts to impose restrictions on federally funded research or the operations of federal science agencies based on premature conclusions about how the pandemic emerged."

Based on what I've seen, I don't know that it will be possible to find the political will to make pathogen research safer before we get a better handle on where SARS-CoV-2 might have come from. The same type of research that might have led to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 continues to be heavily funded and conducted across several countries.

I hope that our book will mobilize the public and the scientific community to call for a new moratorium and new framework for regulating risky pathogen research.

Think Global Health: In Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19, the timeline seems essential evidence. To what extent did you see yourself documenting the origins of COVID-19 to empower others to take the torch forward in the future?

Alina Chan: I don't think anyone could have predicted my pandemic experience. This has been an extraordinary series of events—both on a personal and global level. I had no idea I would end up writing a book on the origin of COVID-19. However, by May 2021, it had become apparent to me that a book on this topic, summarizing the key facts surrounding both natural and lab origin hypotheses was necessary and urgent. It could not wait another year or decade for a book on this topic to be written.

We hope that the book will serve as a resource to the investigators who will conduct a credible and objective inquiry into the origin of COVID-19. For that reason, our book has an extensive citations section so that readers can fact check or track our sources.

I ultimately committed to co-writing this book out of a sense of duty to the future. So that in the next 5 to 50 years, when another outbreak or pandemic of ambiguous origin occurs, I don't kick myself for not doing more to push for a serious investigation of potential lab-based outbreaks.