COVID-19 unleashed a global wave of health nationalism. In foreign policy, nationalistic approaches dominated state decision-making, as reflected in export restrictions on personal protective equipment and medical supplies. When vaccines became available, states with access to them stockpiled doses for their populations, delaying—if not entirely preventing—immunization campaigns in other nations. COVID-19 also stimulated nationalism within states, with several countries prioritizing their nationals at the expense of nonnationals, whether documented or undocumented. In some situations, governments have excluded undocumented nonnationals from COVID-19 interventions, including vaccines and economic assistance.

This surge of health nationalism has revived doubts that international law safeguards the universality of human rights during health emergencies. Blocking exports of critical medical supplies or hoarding vaccines exacerbates the health and economic damage pandemics inflict in other countries. Excluding nonnationals from domestic pandemic responses adversely affects not only the right to health but also the rights to freedom of movement and to work when exercising those rights depends on an individual's vaccination status. During health emergencies, does international law require states to cooperate in the realization of the right to health of people living in other countries? Does international law oblige governments to ensure the human rights of nonnationals living within their territories?

Does international law oblige governments to ensure the human rights of nonnationals living within their territories?

Answering these questions reveals that ambiguities in international law provide opportunities for health nationalism that harm human rights during serious disease events. This conclusion creates a challenge for international human rights law.

Beggar Thy Neighbor, Legally

States parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) must secure the right to health of their population, which includes using vaccines when they are available. However, the ICESCR does not impose a clear obligation on states parties in relation to the right to health of individuals living in other states parties. The ICESCR's general obligation for states parties to take steps, including through international cooperation, to achieve the realization of economic, social, and cultural rights provides a weak and controversial basis for claiming that health nationalism practiced by states parties during COVID-19 violated international law.

Similarly, the most important international legal instrument for responding to outbreaks—the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO)—only contains a general obligation to "undertake to collaborate with each other, to the extent possible." This duty does not provide a strong basis for claiming that nationalistic policies on scarce medical supplies and vaccines during a pandemic violate the IHR. Further, international trade law has supported health nationalism. Export restrictions on medical supplies implemented by members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been consistent with WTO rules. The need to obtain a waiver of patent rights protected under the WTO's Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) to increase global vaccine production and equitable access has benefited vaccine nationalism.

Leave Some Behind, Legally

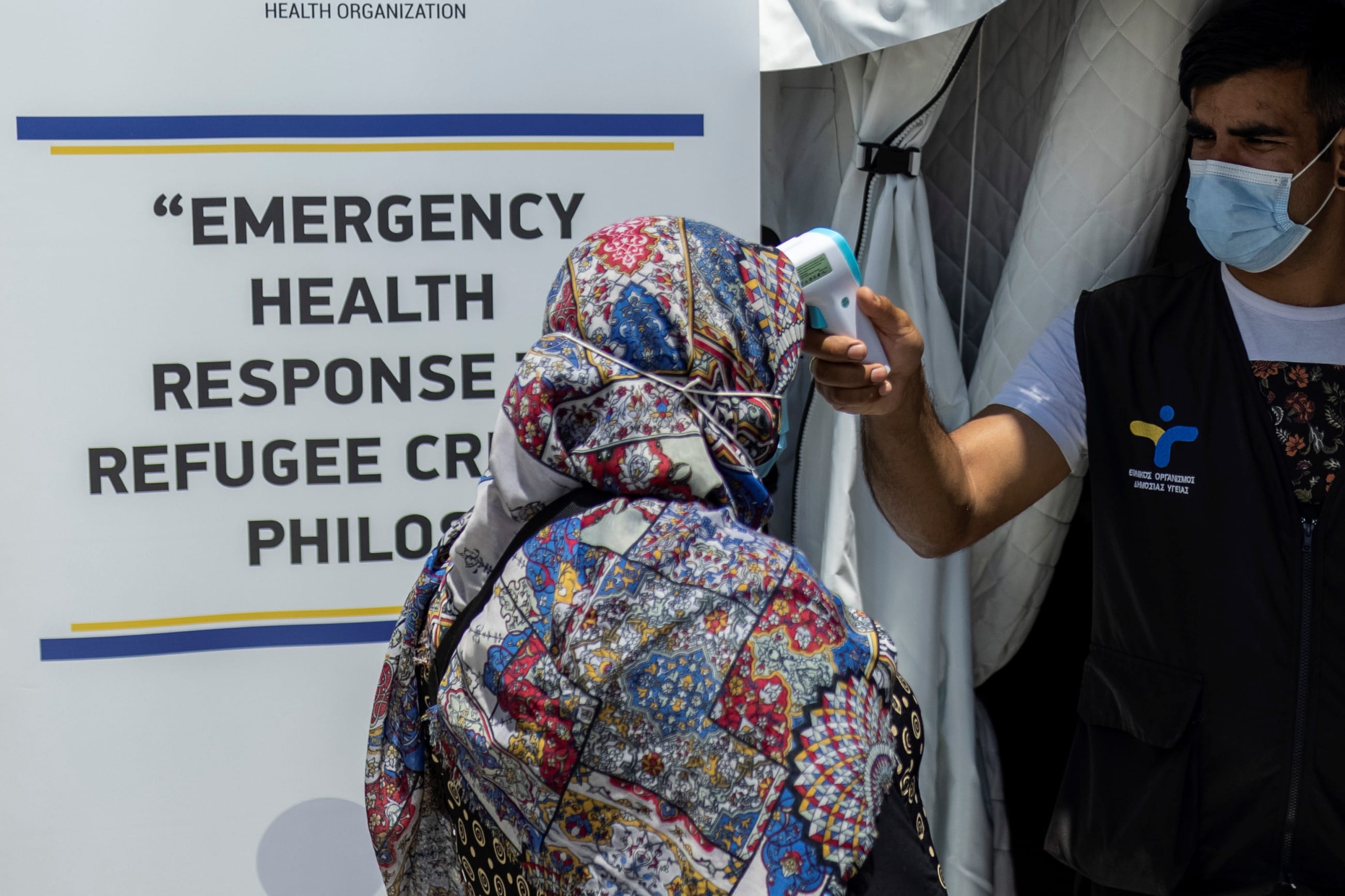

Turning to domestic health nationalism, the ICESCR requires that states parties progressively realize and guarantee the covenant's rights "without discrimination of any kind," including on national origin. However, the progressive realization duty highlights that states parties will sometimes have insufficient resources. Other human rights instruments indicate that differential treatment based on nationality in times of resource scarcity is permissible. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination does not "apply to distinctions, exclusions, restrictions or preferences made … between citizens and non-citizens." The UN General Assembly declaration on the human rights of nonnationals provides that the right to health protection and medical care is conditional on its not placing "undue strain" on state resources. Health measures taken under the IHR must be implemented in a "non-discriminatory manner," but this obligation applies to measures used with travelers rather than nonnationals already living in a country. These examples suggest that international law does not protect nonnationals from discrimination in health contexts when states lack sufficient resources.

All Are Equal, Rhetorically

In responding to the pandemic, international institutions have aggravated the controversies about international law and health nationalism. Indeed, international organizations have stressed the need for cooperation in curbing the spread of COVID-19 and have urged states to cease hoarding medical supplies and vaccines. To counter health nationalism, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank Group, the WTO, and the WHO jointly developed a coordinated plan to vaccinate the world as a way to defeat the pandemic through vaccine equity.

All people in the territory or under the jurisdiction of a state, regardless of their nationality or migration status, have an equal right to health

UN Office, High Commissioner for Human Rights

Similarly, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has asserted that "all people in the territory or under the jurisdiction of a state, regardless of their nationality or migration status, have an equal right to health," and that "scarcity of resources is not a sufficient basis for treating migrants' health-care needs differently." Although giving specific groups priority access to vaccines and other scare medical supplies is inevitable, the UN and regional human rights bodies have argued that the "prioritization of vaccines delivery should not exclude anyone on the basis of nationality and migration status."

However, these statements from international institutions have lacked sufficient legal justification, leaving the door open for states to use the ambiguities and flexibilities in international law described above to justify nationalistic strategies. Most statements issued by international organizations have lacked any reference to states' international legal obligations or merely listed treaty articles without tackling the problems that interpreting those provisions encounters. For example, statements on cooperation and universal access to vaccines do not address the relationship between states' obligation to cooperate under international law and states' rights under international trade law. The statements do not even provide a firm legal basis for a duty to cooperate as a starting point.

Getting to Universality, Legally

The pandemic has exposed the human rights harms produced by health nationalism and has, as a result, strengthened commitment to "leaving no one behind" during serious disease events. This commitment should be translated into a better international legal framework for the protection of the right to health for nonnationals during public health emergencies. This framework requires strengthening the obligation to cooperate with other states in realizing the right to health across borders and the duty to avoid discrimination against nonnationals at home.

Given the prevalence of health nationalism during the pandemic, political opposition will arise to moving international law more clearly in the direction of the universality of the right to health during dangerous outbreaks. However, progress on international human rights has been made in the past despite political resistance. Therefore, strengthening the legal framework for the protection of nonnationals during public health emergencies does not have to wait for any negotiations on a pandemic treaty or amendments to the IHR to start. Rather, international institutions, particularly international human rights bodies, have the responsibility to clarify the seeming ambiguities in existing international law in favor of the universality of the right to health. These interpretations shall in turn provide a robust advocacy tool for the protection of nonnationals in this pandemic and future outbreaks.