Last month, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken hosted the first meeting of the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drugs. Ministers from more than eighty countries committed to strengthen the "global response to the international public health and safety challenges posed by synthetic drugs."

The coalition is a "time-bound twelve- to eighteen-month effort" to "complement, not duplicate or supplant" existing international drug control regimes. It will "offer new solutions" to inform high-level political events, such as the September 2023 UN General Assembly and the March 2024 meeting of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs.

The initiative's driving forces are the U.S. opioid addiction crisis and the threats that synthetic drugs and their chemical precursors also pose to other countries. The need for national and global action against illicit narcotics is scarcely new, U.S. efforts to battle domestic drug addiction and international action on drug trafficking being decades old. The Global Coalition's establishment suggests that past efforts at home and abroad are not enough to combat the threat from synthetic drugs, particularly the highly addictive fentanyl.

The opioid-overdose nightmare inflicted $1.5 trillion in economic damage in the United States in 2020

Geopolitics, however, complicate already difficult domestic and foreign policymaking against dangerous drugs. Before the Global Coalition was established, the United States and China experienced difficult relations concerning flows of Chinese-made fentanyl and its precursors into the United States. Bilateral cooperation has broken down amid accusations about where the blame lies. Those geopolitical dynamics make effective domestic and international policies against the synthetic drug threat harder to forge.

American Carnage

At the Global Coalition's launch, Secretary Blinken noted that overdoses from synthetic drugs, especially fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, are the leading cause of death of Americans between the ages of eighteen and forty-nine. He highlighted that the opioid-overdose nightmare inflicted $1.5 trillion in economic damage in the United States in 2020. This level of health and economic damage from opioid abuse has been decades in the making and is an indictment of domestic policy failures on drug addiction.

The Global Coalition's participating governments embraced national actions based on "public health interventions aimed at reducing demand and at preventing and reducing synthetic drug-related harms to individuals and society." Political tensions between public health and law enforcement approaches to drug addiction have long buffeted U.S. domestic policies, a problem that The Economist reported still inhibits effective actions against fentanyl.

Secretary Blinken told the Global Coalition that the Joe Biden administration's National Drug Control Strategy "for the first time . . . embraces harm reduction efforts that meet people where they are and engages them in care and services." Public health experts have long championed such approaches to drug addiction, and Blinken's phrase—"for the first time" —is a reminder of the country's struggle to agree on a policy center of gravity. Even if Blinken exaggerated, he signaled a policy shift in a context in which consensus on how to reduce demand for illicit drugs does not exist and public health is under attack because of the polarized politics of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Transnational Crime

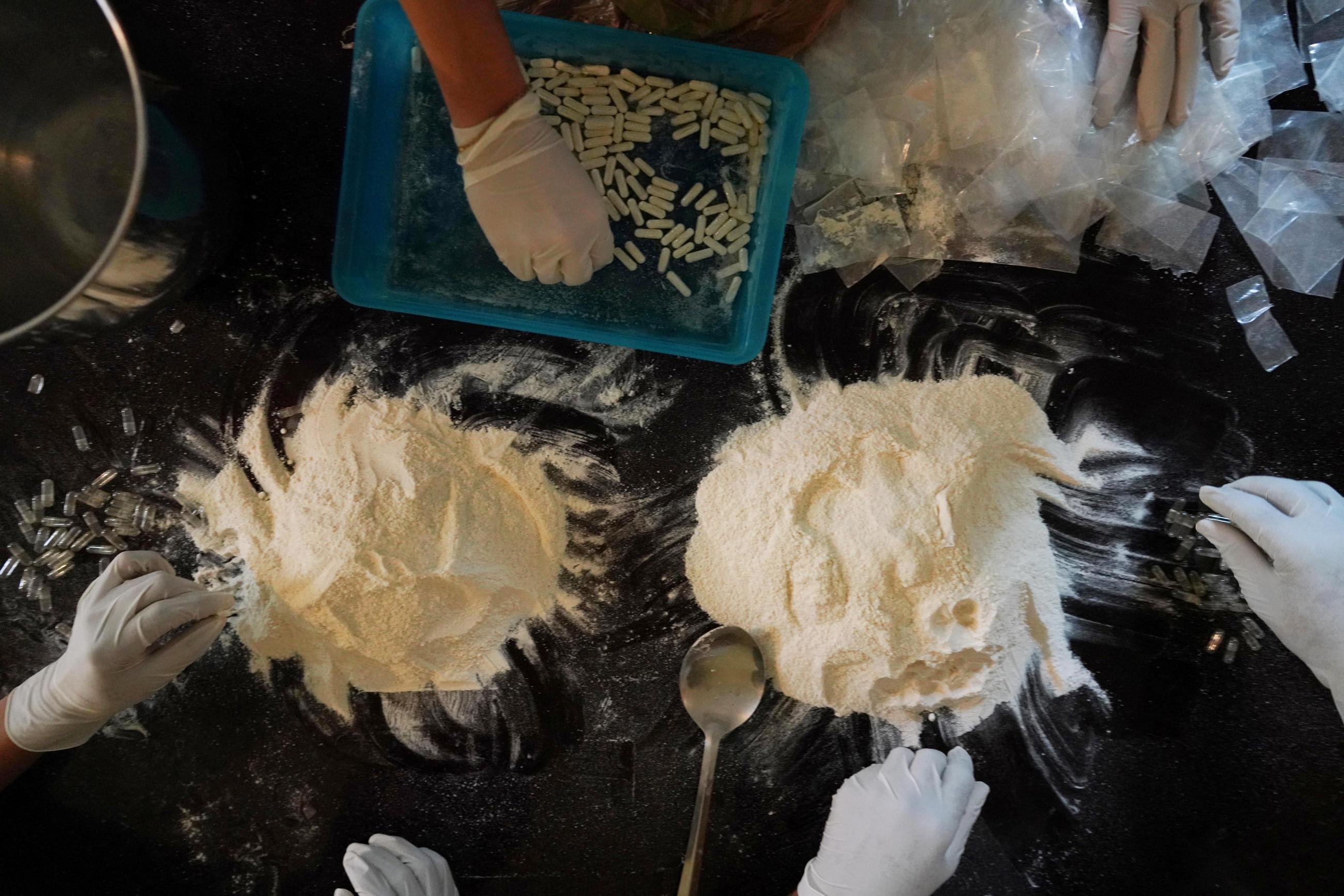

The Global Coalition also committed to prevent and counter the "illicit manufacture, diversion, and trafficking of synthetic drugs and their precursors, including trafficking via the internet." For decades, states have made commitments to fight drug trafficking by transnational organized crime (TOC). The need for another collective-action mechanism to disrupt the transnational supply of another wave of dangerous drugs suggests that past international actions have not worked.

Like U.S. policy, international cooperation has experienced difficulties aligning law enforcement strategies targeting TOC with public health and development programs addressing the root causes of transnational crime. Over time, the United States focused increasing attention on disrupting supplies at their foreign sources rather than primarily at the U.S. border. The tenacity of drug trafficking encouraged the United States to use military resources to supplement law enforcement activities. The role of Mexican drug cartels in shipping fentanyl into the United States has led some U.S. politicians to propose military attacks against the cartels to destroy supply capabilities and deter trafficking.

China perceives the precursor issue as leverage to get something from the United States in another policy area

The troubled history of international cooperation on drug trafficking, and forward-leaning U.S. tendencies, explains why the Global Coalition's declaration emphasizes that supply reduction measures should conform with the UN Charter, international law, the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states, and the principle of nonintervention in the internal affairs of states. Those parameters—combined with the declaration's embrace of existing drug control treaties—raise questions about how this time-limited coalition's ideas will differ in substance and impact from what states have tried for over fifty years.

Opioidpolitik

The origin story of the Global Coalition includes the inability of the United States and China to work together on stemming the supply of fentanyl into the United States. In response to U.S. diplomacy during the Donald Trump administration, China tightened its regulation of fentanyl exports. It did not, however, restrict exports of Chinese-made precursor chemicals used by Mexican cartels to make fentanyl to sell in the United States. China has rebuffed entreaties from the Biden administration to address the precursor problem. Officials and pundits in both countries have engaged in recriminations about allocating responsibility for the U.S. fentanyl crisis.

In short, geopolitics shape U.S. and Chinese foreign policies on fentanyl. The Global Coalition reflects the Biden administration's strategy of developing coalitions of likeminded states to counter China's ambitions. For its part, China has no fentanyl addiction crisis and needs nothing from the United States or the coalition concerning fentanyl control. Instead, China perceives the precursor issue as leverage to get something from the United States in another policy area.

Media reports have described a possible deal in which the United States would lift some human-rights sanctions in exchange for Chinese action against fentanyl precursors. Republican legislators in Congress have condemned the idea of allowing China to use "American lives as a bargaining chip to achieve sanctions relief for its human rights abuses."

Those aspects of the fentanyl controversy echo the geopolitical calculations that also inform U.S. and Chinese approaches to pandemic preparedness and climate change. On none of those three global health issues do the U.S. and Chinese governments have constructive bilateral relations. In global health and other policy areas, the U.S.-China rivalry shrinks the space for bargaining and threatens to render compromise vulnerable to accusations of weakness and appeasement.

Three-Ring Circus

To address the U.S. fentanyl crisis, the Biden administration seeks to shift domestic policy toward a public health approach to drug addiction, catalyze collective action against synthetic drug trafficking, and cajole China into restricting precursor exports. Those approaches are, in theory, synergistic in supporting reduction in the demand for, and illicit supply of, fentanyl and other synthetic drugs.

In practice, the strategy is vulnerable domestically, diplomatically, and geopolitically. The opioid tragedy has contributed to the polarization of U.S. politics, creating doubts that a public health approach to drug addiction will prevail. Adding a temporary coalition to supplement international drug control regimes raises questions about whether it offers something new and sustainable. In geopolitical terms, the United States has the weaker hand because it needs Chinese cooperation to disrupt illicit fentanyl flows into the United States.

Those vulnerabilities suggest that fentanyl control could become a three-ring circus, with domestic, international, and geopolitical activities unfolding under their own dynamics, which, at all three levels, are now more antagonistic than synergistic. In that suboptimal scenario, improving domestic policies perhaps offer more promise than foreign policy does.