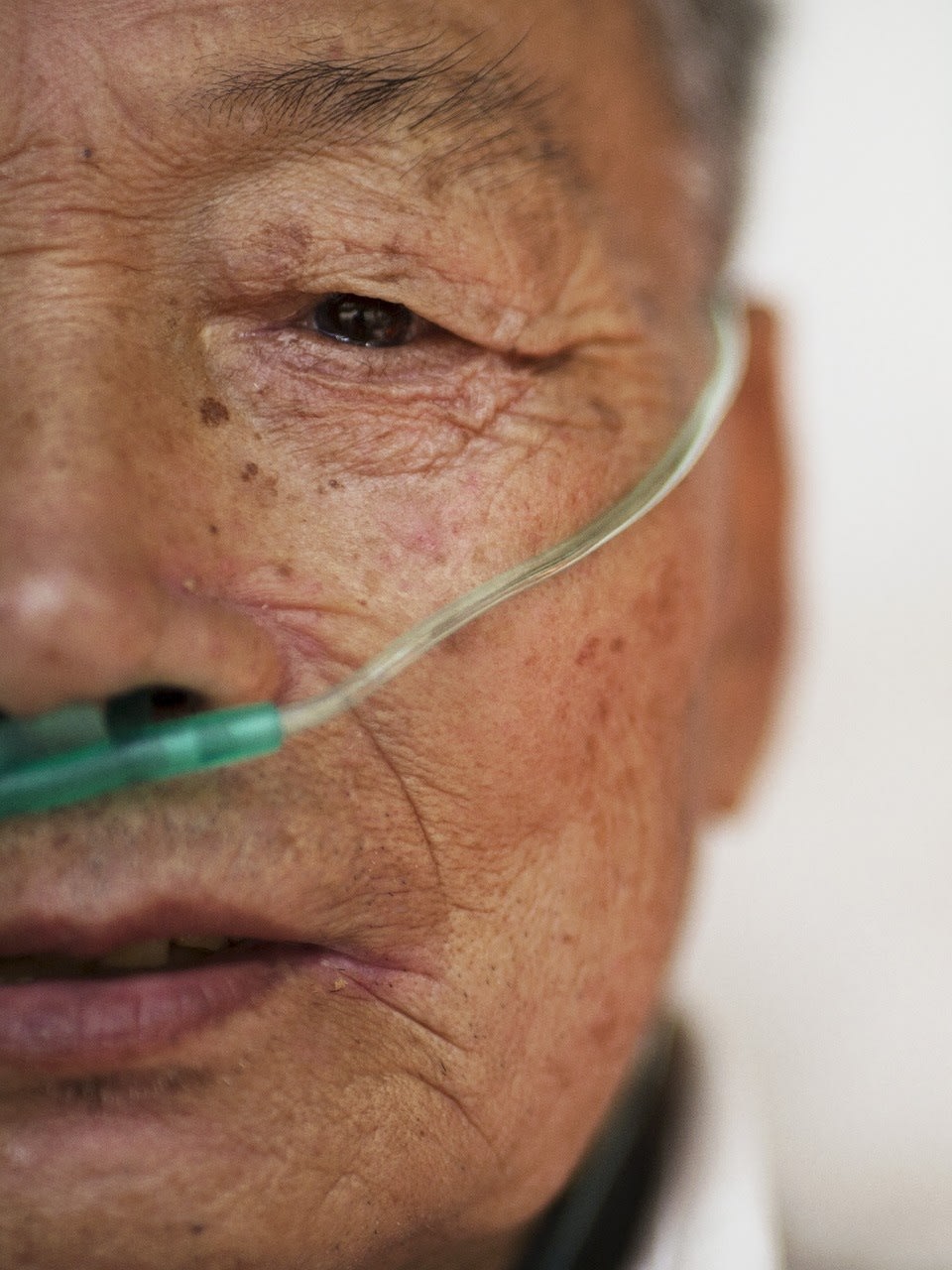

Exhausted and short of breath, Maurine Murenga visited two hospitals in Nairobi, Kenya, before finding a third where she could afford the cost of care with oxygen. Like some one in five people with COVID, Murenga needed concentrated oxygen so that her immune system had time to fight the infection even as her lungs were being damaged by the coronavirus. Murenga, a health advocate, was grateful for the life-saving gas but dismayed when the older women waiting for oxygen beside her were turned away because they could not afford the price of limited oxygen supplies. "People died because they did not have a down payment," she recalled.

Death rates among people hospitalized for COVID-19 in low-income countries were twice as high as in wealthy ones, and a lack of medical oxygen is a core reason for the disparity. The pandemic, though, merely put the need for oxygen on display. For decades, droves of children and adults with pneumonia or tuberculosis had died gasping for air because nurses could not deliver the oxygen they needed.

Death rates among people hospitalized for COVID-19 in low-income countries were twice as high as in wealthy ones

"Losing a patient because you don't have oxygen is one of the saddest things," said Mike Ryan, executive director of the Emergencies Program at the World Health Organization (WHO), speaking on a grassy hilltop down the road from the organization's headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, on May 24. The following day, the WHO passed a resolution urging all countries to add medical oxygen to their essential medicine lists and provide it at clinics and hospitals.

To do so reliably, countries will need many more plants capable of producing medical oxygen, containers to store it at hospitals, and pipes to shuttle it through the facilities. Engineers will be required to maintain the system and nurses trained to operate it. In the heat of the COVID-19 pandemic, many efforts to boost oxygen went toward stand-alone oxygen cylinders instead of an entire oxygen ecosystem because the former require less infrastructure. But this stopgap measure was expensive. Supply chain problems and monopolies on the oxygen market resulted in skyrocketing canister costs. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a reliance on cylinders accounts for why medical oxygen was at least five times more expensive in African countries than in the United States.

Further, canisters have a limited reach. Navin Bhatt, a doctor at Mount Sinai Elmhurst Hospital in New York, who was working at Bayalpata Hospital in Achham, Nepal, during the pandemic, pointed out that people in remote and mountainous parts of Nepal were especially vulnerable. "In the rural areas, where there is a lack of transportation and poor roadways, people have to carry the oxygen cylinders on their backs for more than fifteen hours," he said.

The WHO's resolution attempts to sustain the attention of donors and governments beyond the acute crisis. Just before its announcement, the organization launched the Global Oxygen Alliance, which includes the Global Fund, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, among others. Money remaining from some $1 billion in donations for medical oxygen since 2021 will shift to the Alliance. Independently, USAID is continuing its work on boosting medical oxygen in several African countries, Jamaica, and Vietnam.

Spokespeople from the Alliance and USAID said that their donations, thus far, have been spent on oxygen equipment, oxygen plants, and on training engineers and nurses. They did not answer my more specific, emailed queries asking for a breakdown of their expenditures. Nor did they confirm whether any of the funds went toward salaries for staff, a cost that often goes missing when it's left to local governments. "It is difficult to provide precise data points," wrote Katy Huang, a technical officer at the WHO, in an emailed response. "It is acknowledged that greater investment in human capital and recurrent costs for equipment sustenance is needed," she added.

A degree of uncertainty and efficiency should be forgiven in crisis response, but now that the emergency phase of pandemic has passed, the oxygen boom deserves a more measured approach from donors, as well as from the governments of low- and middle-income countries that scrambled to procure oxygen as their hospitals overflowed and deaths mounted.

In Nepal, for example, the government tried to distribute limited oxygen cannisters that had been stockpiled by those who could afford to do so, recalled Shyam Sundar Budhathoki, a global health researcher at Imperial College London who collaborated with academic institutions in Nepal during surges of COVID in the country. "Our strategy in this crisis was firefighting," he said. He warned that the situation will repeat if the Nepalese government isn't strategic about improving oxygen availability. "Every donation should come with a plan for who is responsible for maintaining and using it."

Now that the emergency phase of pandemic has passed, the oxygen boom deserves a more measured approach

The WHO resolution rightly asks countries to develop national, budgeted plans on boosting medical oxygen, including needed infrastructure and personnel. But what countries require is not obvious, explained Paul Sonenthal, director of inpatient medicine and critical care at the nonprofit Partners in Health, where he oversees an initiative to accelerate access to medical oxygen in a number of countries where they operate.

For example, hospital surveys underestimate needs if they ask whether facilities have oxygen. More accurate information derives from questions such as whether the facilities have enough oxygen to help critically ill patients in the time frame required, Sonenthal said. If a hospital doesn't have enough staff or electricity to operate an oxygen system overnight, for example, the answer is no. Another telling question is whether health workers can identify and treat patients who need oxygen. "That comes down to having pulse oximetry, a system for screening patients for early warning signs, and clinicians with the right skills."

In a report released in February, the WHO suggested other indicators for monitoring oxygen ecosystems, such as the number of patients on oxygen with documentation every eight hours. Organizations bankrolling initiatives should incorporate such measures to boost confidence in their efforts. That's important because over the next decade, more money will likely be needed to make oxygen systems sustainable.

The other reason to carefully assess projects is that there's a lot to lose. Aid organizations boast the enormous number of lives that would be saved from medical oxygen and how that would help the world reach the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. But an oxygen plant won't produce those improvements on its own. Oxygen is vital and conceptually simple, but providing it requires sustaining a system. The real innovation—the true novel approach—would be rising to that challenge.