Globalization is changing and it is affecting where and how medicines are produced.

Great power competition between the United States and China has brought about a rise in economic nationalism and a corresponding decline in the liberal rules-based international order. The resulting shift in economic focus from cost-efficiency to security, resilience, and risk management has fundamentally altered supply chains and trading relationships. The media has focused disproportionately on changes in the production of semiconductors and goods that are or could be capable of military use, but the manufacture of medicines is also undergoing a transformation.

Both the United States and European Union are actively seeking to ensure medical supply security. For instance, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States issued an executive order to accelerate domestic manufacturing and address supply chain vulnerabilities of essential medicines. More recently, President Joe Biden announced funding for a biotechnology and biomanufacturing initiative. For its part, the European Union recently broadened the scope of national security-related measures, and several member states have proposed a Critical Medicines Act to mirror the European CHIPS Act and Critical Raw Materials Act.

COVID led many countries to reevaluate their dependencies for critical goods and services

Several related factors have driven this shift to medical supply security. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in global supply chains, leading many countries to reevaluate their dependencies for critical goods and services.

American perceptions of China have also shifted from a benign manufacturing base to a strategic competitor. Globalization once meant the pursuit of cost-efficiency by extending networks of investment and production to harness the comparative advantages of different geographies—but a consensus is growing that overreliance on a potential geopolitical rival for critical supplies is not in the national interest.

Moreover, reflecting a growing trend of promoting manufacturing and industrial policy, the United States and European Union are plying the pharmaceutical sector to invest in new production facilities and increase employment. For instance, President Biden pledged $2 billion over five years to increase domestic production of pharmaceuticals, from key starting materials and active pharmaceutical ingredients to finished dosage forms, which he said would "create good jobs and strengthen supply chains." If successful, this would mark a large shift from America's current focus on packaging and filling.

Unpacking Global Supply Chains

Despite the burgeoning interest in it, the domestic production of medicines is not without challenges. First is that pharmaceutical supply chains are now exceptionally complex, involving numerous countries at different stages of production. Production dynamics are also well entrenched and may only be altered with significant subsidies or tariffs. Bringing the entire supply chain into Europe, for example, may neither be feasible nor efficient, particularly given the cost advantages in countries such as China and India.

Until the mid-1990s, the West and Japan produced 90 percent of the world's active pharmaceutical ingredients. In the 2000s, as globalization quickened, companies reduced manufacturing costs by sourcing ingredients from China and generic medicines from India. Acknowledging the industry's eastward shift, the Chinese government passed legislation and enacted regulations to further promote it, including the 2005 Administrative Measures for Drug Registration. Beijing continues to recognize the economic importance of the active pharmaceutical ingredients industry, as indicated by a November 2021 statement from China's National Development and Reform Commission emphasizing the long-term strategic advantages they confer in the global marketplace.

Risk of Market Distortion

A number of European countries are seeking to shift supply chains toward Europe, support domestic pharmaceutical industries, and foster the production of certain essential drugs, and the European Commission is likely to act on the proposal. The passage of a Critical Medicines Act could distort the global market in a number of ways. The primary risk is that other countries will provide their own subsidies to attract domestic production, leading to the fragmentation of supply chains, reducing efficiencies, and shifting costs to governments. Such intervention could affect global prices and threaten the viability of smaller, independent manufacturers and those located in countries where governments are not providing inducements or price supports.

Another risk is that countries will invoke national security as a smokescreen for their genuine motives of protectionism, shifting production from competitive countries to U.S. and EU manufacturers. This might violate the World Trade Organization's (WTO) agreement on subsidies, should it include a financial contribution that provides a benefit and impacts competition.

Problems associated with pharmaceutical distribution will not be resolved if each country prioritizes production for its domestic supply

The Principle of Shared Responsibility in the Pandemic Treaty: Implications and Challenges

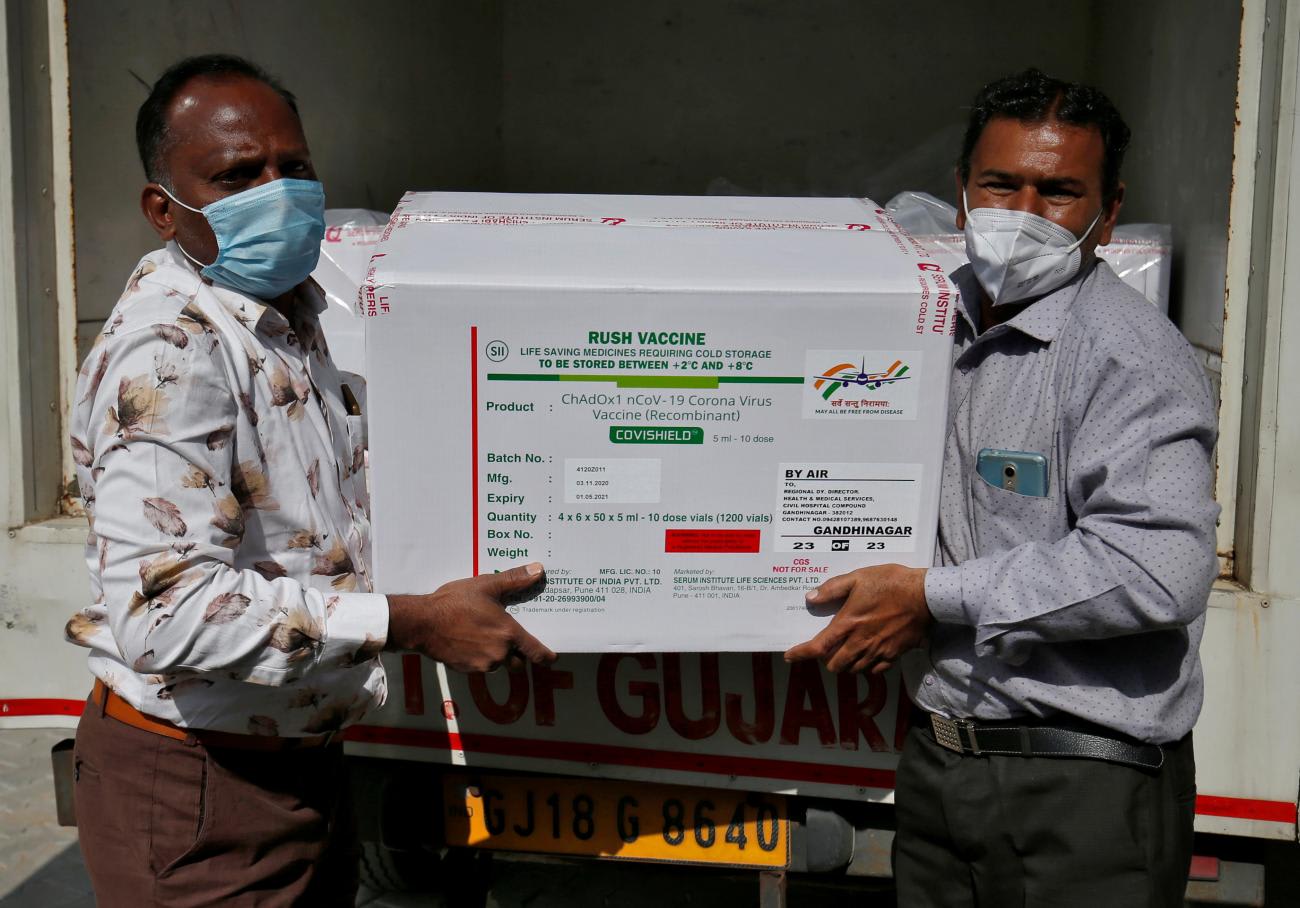

The need for a coordinated global approach to ensure equal access to life-saving vaccines and treatments is urgent. During the pandemic, inequality in worldwide access to COVID-19 vaccines was on stark display. The problems associated with pharmaceutical distribution will not be resolved if each country prioritizes production for its domestic supply.

A draft global pandemic treaty being negotiated at the World Health Organization incorporates a principle rooted in international environmental law known as "common but differentiated responsibilities and capabilities." The principle recognizes that all nations are obligated to tackle global issues such as climate change or pandemics but that their capacities to do so vary substantially.

In pharmaceuticals, this principle recognizes that the world shares responsibility to ensure everyone has access to crucial medications, but nations differ significantly in their ability to manufacture medicines or import supplies. The draft treaty recommends establishing "strategic stockpiles" of pandemic response items at regional and national levels. The proposal suggests that international hubs and regional staging areas could streamline the supply chain, facilitated by multilateral and regional purchasing mechanisms.

Application of the principle faces several challenges. Some developed nations argue that the principle is relatively unknown within global health law and could be ineffective in addressing public health emergencies. In contrast, developing countries contend that a worldwide health crisis is a shared threat, just like a climate emergency. Proponents also point out that the principle can be traced to other treaties, such as the "special and differential treatment" provisions in the WTO agreements and Articles 203 and 278 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Moving Forward

Whether for good or ill, countries are shifting their supply chains for medical supplies and treatments towards greater self-sufficiency and resilience. This shift could enhance public health preparedness during crises but may also disrupt global market dynamics and inflate costs. The pandemic treaty under negotiation could help by enhancing the capacity of the World Health Organization (WHO) to oversee and coordinate international health efforts. But it's unclear whether WHO is up to the challenge.

AUTHORS' NOTE: This research is supported by the Hong Kong RGC Senior Research Fellow Scheme 2022/23 for a project entitled: Access to Vaccines in a Post-COVID-19 World: Sustainable Legal and Policy Options (Project No. SRFS2223-4H01). The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of others involved in the project.