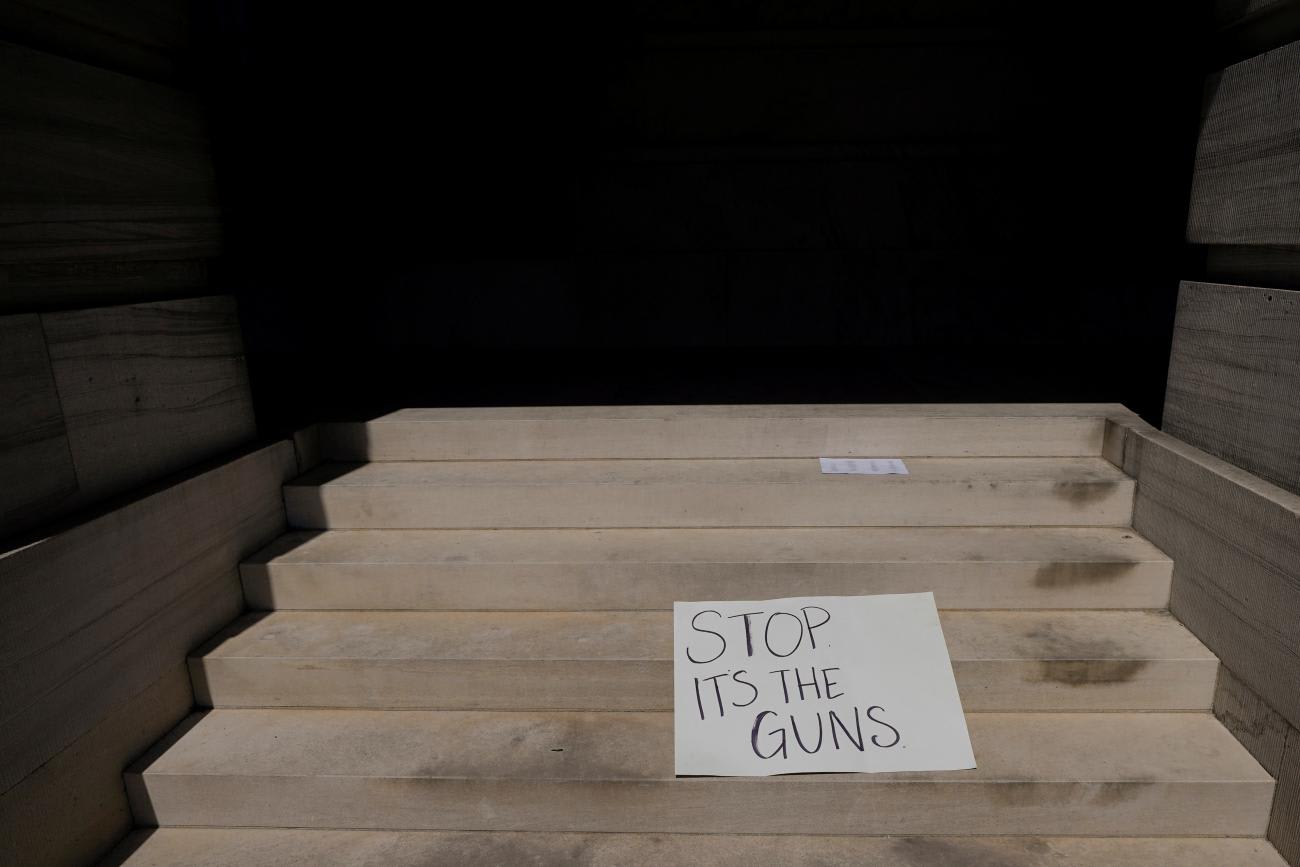

Gun violence occurs with exceptional frequency in the United States, but firearms manufactured in the United States also turn up at crime scenes in neighboring countries. Some anti-violence advocates increasingly argue that the country should be held responsible for this harm — and that international law might also be a powerful tool for reforming the U.S. gun industry where domestic law has fallen short.

Among them is litigator Jonathan Lowy, who has spent twenty years in the gun violence prevention movement trying to hold U.S. gun companies accountable for a greater share of the violence created by their products. He recently founded Global Action on Gun Violence (GAGV), a nonprofit working on the behalf of foreign governments, and spoke with Think Global Health about why he sees an opportunity in this new arena.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What processes drive gun violence, and what role can litigation play in disrupting them?

Jonathan Lowy: In my career, I have mostly focused on the role of the gun industry, which I think is the major driver of gun violence in the United States, and in some sense the world. Some gun laws are weak and should be strengthened. The fact remains, though, that gun companies could and should choose to make and sell guns in a more responsible way, regardless of what the law allows.

Instead, manufacturers and dealers choose, for the most part, to make and sell guns in such a way as to maximize sales. These sales include guns that end up with criminals, organized crime cartels in Mexico, and other people who shouldn't have them. That, obviously, is a massive driver of gun violence.

Manufacturers and dealers choose, for the most part, to make and sell guns in a way to maximize sales

Think Global Health: How much have gun violence prevention advocates focused on the gun industry?

Jonathan Lowy: [For most of my career] the overwhelming focus has been on legislation but I think that recognition is growing that the gun industry is a major part of the problem and that reforming the gun industry through litigation and other pressures could be especially effective.

Think Global Health: How have legal strategies waxed or waned in effectiveness?

Jonathan Lowy: Thirty years ago, litigation [was widely recognized as] an important tool for many public health crises. It's been an important tool in dealing with tobacco, opioids, and even motor vehicle deaths. Litigation was also becoming an extremely effective way to deal with [the gun violence] problem. In 2000, litigation led [the gun manufacturer] Smith & Wesson to agree to sweeping reforms to its sales, distribution, and marketing practices, well beyond what any state or Congress required.

The gun industry and the National Rifle Association (NRA) saw this as a threat to their ability to profit from the criminal market and thus pushed for federal legislation. In 2005, the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, referred to as the PLCAA, was enacted, giving the gun industry special protections from civil liability that no other industry in America has.

The PLCAA has not prohibited legislation or litigation, and some litigation since it was enacted has been successful, but it has certainly made litigation more difficult. Strategies — both litigation and legislative — are available, though, that can address the situation to some extent. One of these is litigation by foreign actors.

Think Global Health: How does foreign actors' involvement change things?

Jonathan Lowy: The fundamental strength of an international approach is it escapes the political constraints of the United States, which can be limiting. You're dealing with laws like the PLCAA, but an international constraint can expand the agenda of what's possible given how warped gun politics are in the United States.

The idea, accepted by some Supreme Court justices now, is that gun rights are fundamental but the human right to live [is] not so much. That concept is crazy to the rest of the world. It should be. A serious debate should not be held about which is more important, the right of a child to live or the right of a gun manufacturer to profit from assault weapon sales. The notion is controversial in many sectors in the United States, however. I think getting away from it really opens up that conversation, the agenda.

As a legal matter, arguments that gun industry special protection laws do not apply when action is brought for harm suffered outside the United States are strong. We're making that argument on behalf of the government of Mexico in two cases in U.S. courts. In candor, the trial court [in] the first case rejected those arguments, [so] we're now an appeal, we're hopeful that the appellate court will reverse it. But the strategy is promising.

Think Global Health: What's the argument that you are making in those cases?

Jonathan Lowy: The two Mexico cases address the issue of the gun industry's distribution of firearms in a way that supplies a criminal market. The theory is similar to arguments U.S. cities made in the late 1990s when they brought lawsuits against major gun manufacturers: that the manufacturers know precisely how their guns supply the criminal market. Manufacturers have been told that those guns are generally sold by a small percentage of gun dealers; they also know that the criminal gun market is supplied through certain reckless practices — bulk sales of guns, repeat sales of guns, straw purchases. Yet manufacturers choose, deliberately choose, to use exactly those dealers and those practices they've been told will supply the criminal market. They don't have to, they shouldn't, and in fact they've been told they should have standards for their dealers and not supply reckless or corrupt ones. Again, however, they choose not to consider or establish standards. Such a choice is negligent, is reckless, and is unlawful.

Mexico is making legal arguments that are not available to domestic lawsuits — extraterritoriality, for one. You can't read U.S. law as a sort of safe haven where companies can engage in conduct that injures neighboring countries, yet these companies can retreat behind the walls of U.S. law, where they're shielded from all accountability.

Think Global Health: What about the Canadian case?

Jonathan Lowy: It addresses a different issue, specifically, the design of guns. In that case, the theory is not how the gun is sold, but how the gun is made.

Human rights is not just a sort of free-floating concept or rhetoric. There are international treaties and conventions.

Guns are the only consumer product [in the] United States not subject to federal product safety regulation. For every other product, federal agencies such as the Consumer Product Safety Commission can require that a product have lifesaving safety features. They can't do that with guns. As a result of that and the decision of the gun industry to not include these physical safety features, guns are more than one hundred years behind the times in safety devices.

In the Canada case, the theory is that the gun used in that mass shooting could have and should have included safety features, which were clearly feasible, that would have prevented the criminal who was sold the gun from firing it and that would have prevented the shooting. That sort of safety device would save many lives, not just in preventing guns from being transferred to the criminal market but also in preventing children finding guns in the home from shooting themselves or others. Those guns simply would not fire. Just as if someone took your iPhone but couldn't use it or was able to get into your car but didn't have the key and so couldn't drive.

Think Global Health: How have U.S. courts typically treated a proverbial "right to life" relative to firearm rights?

Jonathan Lowy: A number of years ago I cowrote a law review article titled "The Right Not to be Shot" that argued that all constitutional rights are constrained in some way by public safety. Although the Supreme Court has rarely explicitly recognized the right to live, the justices do in fact recognize it. For example, there's no right to cry "fire!" in a crowded theater. We're not going to give people individual rights to endanger the lives of other people. In that article, I argue that the Second Amendment has to be similarly constrained in the context of a potential right to possess a lethal weapon. The Constitution is not, as Justice (Robert) Jackson said, "a suicide pact." It's not a homicide pact, either.

GAGV is making this argument in the international community, including the American Commission on Human Rights, the Organization of American States, and bodies where treaties and conventions impose obligations on the United States to protect human rights, including the right to live. In our view, it is impermissible for the United States to have gun policies that endanger those fundamental human rights.

The U.S. gun industry is a significant international crisis and should be treated as such by the international community. The United States has obligations to address that crisis in a responsible way — under the Constitution, properly understood, but also under international and human rights law.

Think Global Health: What is your thinking about how human rights law could be a lever for addressing gun violence?

Jonathan Lowy: Human rights is not just a free-floating concept or rhetoric. International treaties and conventions are in place — some of which the United States is a party to, and others that are sort of halfway — that support the idea that what the United States is doing in allowing the gun industry to sell assault weapons to eighteen-year-olds, to sell guns with very little vetting, without any limit, to people without any training, without any licensing, violates human rights.

I'm hopeful in the coming years we'll be seeing international tribunals state that U.S. foreign policy violates its human rights obligations, its international law obligations. I think that will be a powerful pressure point to change U.S. policy.

Think Global Health: Legally, what do you need to show to secure that confirmation by international bodies?

Jonathan Lowy: As in civil litigation, where we often solicit amicus briefs from different communities and different public health and law enforcement experts, in the rights realm you need to make clear to the decision-makers the scope of the problem. In an international setting, it's important to make the case that U.S. gun policy leads to gun trafficking, which facilitates drug trafficking, which facilitates all the organized crime activities. It spurs migration, it impedes economic development and other efforts at social progress.

Think Global Health: What have your interactions been like with your international clients?

Jonathan Lowy: Universally, enthusiasm has been tremendous. I've spoken at conferences and meetings around the world and excitement about it is considerable because recognition of the problem has been long-standing but without much focus on the gun industry and how that actually facilitates these problems. A month or so ago, I spoke at a conference of Caribbean Community leaders, which was attended by many prime ministers. These leaders said we don't make guns and yet we have this huge gun violence problem, almost entirely from guns coming from the United States. After that conference, the leaders announced goals about how their gun laws should be strengthened, but also asserted that the United States needs to do more.

We've also seen a number of high-ranking U.S. officials recognize that, stating that the United States does have a responsibility to do more to prevent the flow of guns to Mexico and to the Caribbean.

Think Global Health: How do you see litigation interfacing with other ways of addressing gun violence?

Jonathan Lowy: It's critical that domestic gun violence prevention efforts in the United States continue, and great work is under way. One thing we're seeing that's very promising is the growing number of states enacting laws that can impose greater liability on the gun industry. I think all these factors work together: increased international pressure, increased domestic pressure, and a changing demographic that's more supportive of gun violence prevention. I think it's going to lead the United States join the rest of the world in protecting the right to live.