The detection of H5N1, a highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza virus, in dairy cows on Kansas and Texas farms in late March marks the first time this concerning flu subtype has been detected in the species. As of May 9, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has confirmed cases in 36 dairy herds across nine states, associated with a single human case. Although identification in dairy cows and goats—and the consequent media attention—is new, this strain has been responsible for a global epidemic in birds and other mammals since 2020.

As the United States grapples with policies to address the outbreak, scientists are struggling to understand why the outbreak seemingly took the USDA and other federal agencies by surprise. Avian influenza is becoming an endemic threat to the country, making current efforts inherently reactionary. The crisis in wildlife does not seem to be improving. Downplaying the influence of this sustained outbreak in dairy cows, the relentless infection of poultry, fatal cases in cats and other mammals, and the potential for additional spillover may create risks to lives and livelihoods.

Should this influenza virus adapt to human transmission—a possibility that continued mammalian transmission will test again and again—the consequences will play out on both global and domestic stages even as One Health components of the pandemic accord negotiations look likely to be pushed to future deliberations.

The pivot point is now—or a month ago. Indeed, calls for aggressively increased surveillance in animals since early 2022 have gone unheeded, creating blind spots that may be fueling the current situation.

From Millions of Birds to Cows

Studies show that cattle are susceptible to influenza, including zoonotic strains that jump between animals and people. This particular clade of H5N1 has infected and killed a wide range of mammals, from red foxes and skunks to cats and goats. Across North America, these mammals, both wild and domesticated, share space and sit beneath the flyways of infected birds.

The H5N1 outbreaks in the dairy industry and wild mammals occur alongside the recent surge in commercial poultry cases: in 2024 to date, more than 9.2 million commercial and backyard flock birds across the country have been affected (that is, died or were depopulated), the tally in April alone accounting for nearly 9 million of these animals. Since 2022, 90.89 million birds have died from infection or been culled as part of the government's stamping out policy.

Cows likely were moved among farms for at least a month—likely longer—after the outbreak began

Meanwhile, confirmations of H5N1 in wild birds have continued, with pigeons, blackbirds, and grackles identified dead on affected dairy farms. Transmission from infected cows to cats on farms and nearby poultry facilities highlights the ability of this virus to spread among mammal species and back to birds.

The confirmed case numbers in cows likely underestimate the actual incidence of infection considerably considering the detection of noninfectious H5N1 particles in pasteurized milk on store shelves. As the number of small dairy farms decreases in favor of larger, consolidated operations, an affected farm could see rapid spread to larger numbers of animals.

Much of the ongoing surveillance in the more than 9 million head of U.S. dairy cows continues to be based on voluntary reporting of ill cows from individual farms; a challenge given that approximately 10 to 15% of dairy cows on affected farms appear to be impacted, showing a range of nonspecific clinical signs. The USDA issued a federal order effective April 29 requiring a negative influenza A test—from an approved National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) laboratory—to allow interstate movement of cattle.

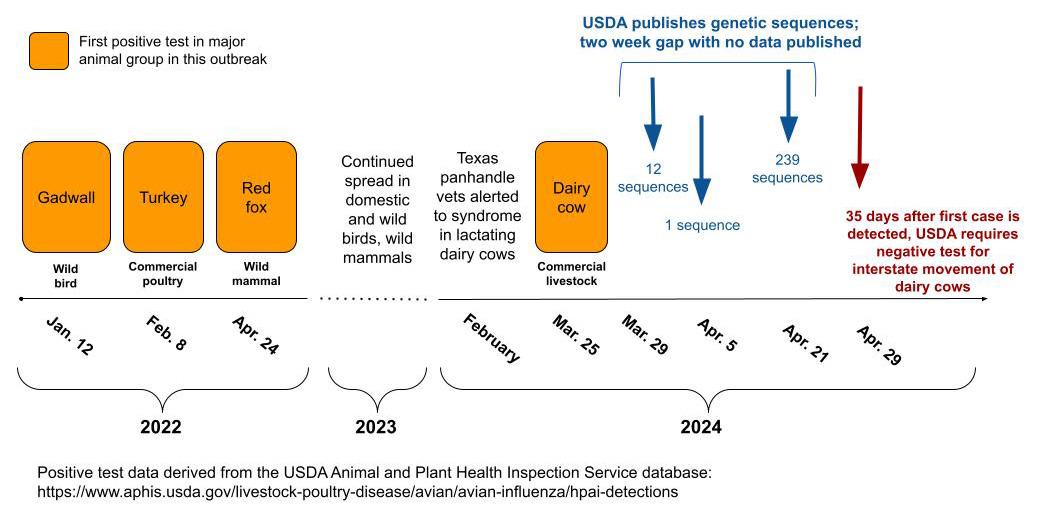

Given that symptoms were identified in February and confirmed in March, cows likely were moved among farms for at least a month—likely longer—after the outbreak began. Beyond what is captured by NAHLN, no public database reports the interstate movement of cows. This undoubtedly will challenge both federal regulators seeking to enforce the federal order and as scientists who could help model the spread of infection via interstate commerce. Another important need is proactive testing and tracking of beef cattle, swine, goats, and sheep, given the likely or potential susceptibility of these species to HPAI.

Incentives for dairy farmers to report symptomatic animals and workers for health evaluation and testing have been limited for over a month—and were just recently expanded on May 10 to include indemnification for lost milk production, more comprehensive reimbursement for costs of testing, and limited funds to improve biocontainment.

Although surveillance in beef cattle has begun (driven primarily by testing of retail meat products), sampling of other livestock such as goats, sheep, and swine is not well documented federally on the USDA dashboard as of May 10, despite the demonstrated susceptibility of goats and pigs.

Also lacking from the guidance is the consideration of requiring pooled testing of farms, whether they be dairy, poultry, or swine; environmental sampling (bulk milk, manure, or litter); or strategic testing based on, for instance, proximity or networks.

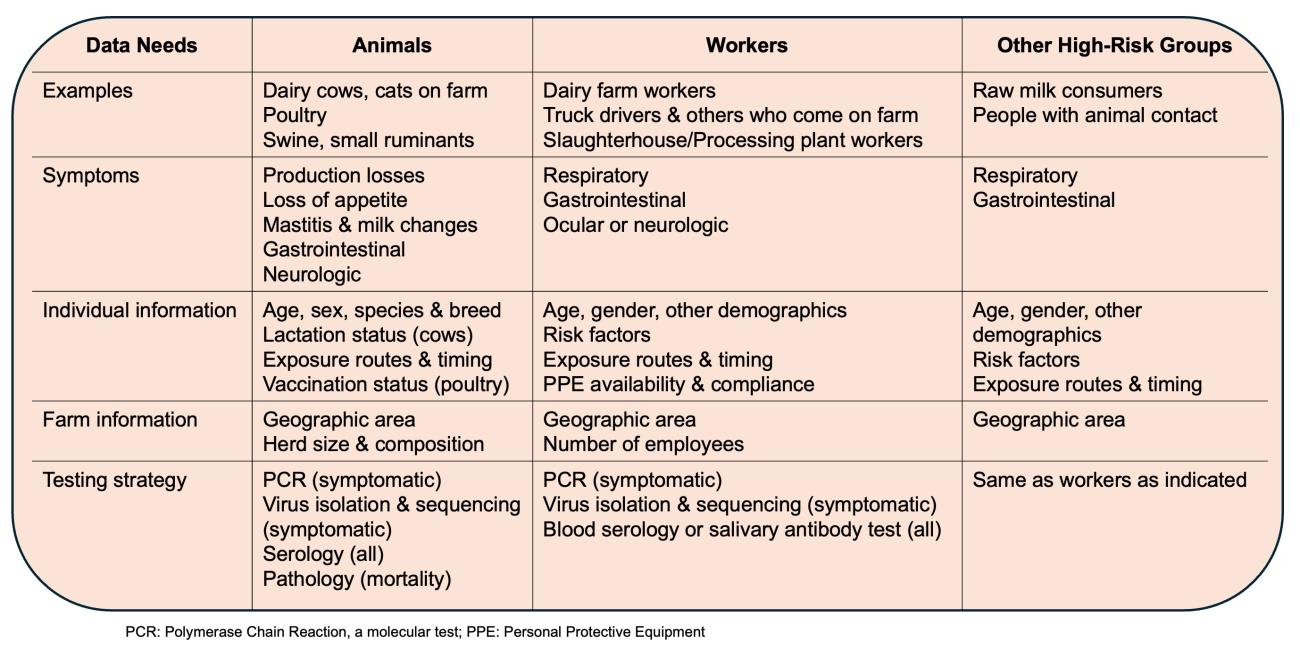

Even though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasizes that the risk to the general public is low (though it could be higher for raw milk consumers), enhanced surveillance, mitigation, and response are needed at the animal interface and among high-risk groups, which can be achieved in noninvasive ways such as salivary antibody testing, similar to efforts in other animal worker cohorts.

Reemerging Policy Issues Accompany an Emerging Infection

The initial response and availability of information for both the research and public sectors was unacceptable. Delays were significant in data sharing of genetic sequences obtained from various positive species (see timeline), including a 15-day gap during which hundreds of samples were sequenced without being posted. When officials ultimately posted the information, it lacked key details, such as the date and location of collection (known as metadata).

Yet the value of publicizing the data was immediately proven by the important insights it enabled, including one analysis (not yet peer reviewed) that suggested cows may have been infected as early as December 2023. Such analyses by outside experts are subverted by gaps in critical epidemiological metadata; for instance, these shortcomings do not allow insights into the transmission links between farms or the geographic identification of affected species and migratory flyways.

It is unclear why the USDA would delay release of the sequences or exclude important metadata, particularly given that this outbreak comes on the heels of the many lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic regarding data collection, transparency, and risk communication. The simplest reason may be that the department has dual mandates—one on protecting and promoting animal markets, and the other regulatory.

Farmers made up more than half of the nation's population when the USDA was established in 1862 to perform research and education. Its founding signaled a government desire to support American agriculture through research and other programs, which grew into institutionalized support for agricultural markets. The establishment of the Bureau of Animal Industry within the department in 1884 marked the beginning of the shift toward including regulatory authority in its mandates, with oversight for the "protection and use" of livestock, including investigating and reporting on infectious diseases specifically in relation to commercial interests.

The USDA has interests that at times compete: supporting farmers and food animal production while investing in public health-oriented responsibilities. For instance, its Agricultural Marketing Service runs the Dairy Program, the purpose of which is to "facilitate the efficient marketing of milk and dairy products." It is a market promotion program, not a public health or animal health program beyond the extent to which its investments in animal health directly support the dairy commodity market. Yet the USDA's regulatory arm—the Food Safety and Inspection Service—is very much a public health organization, similar to the Food and Drug Administration or CDC.

Can the two roles be effective within a single agency? Conflicts exemplified by these internal tensions have arisen before and will continue to do so. Given not just these conflicting roles, but also the way oversight of animal health is spread among many agencies, it may be time to consider a more significant overhaul.

The USDA has interests that at times compete: supporting farmers and food animal production while investing in public health-oriented responsibilities

The current status of One Health coordination across the federal interagency is not preventing the significant problems occurring now. Can this coordination be accelerated in the near term and prove effective, perhaps under the oversight of the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy? If this approach does not work, the fallback may be to consider a consolidation of animal health and outbreak response for all species, from livestock to domestic animals to wildlife, into its own agency.

USDA lists H5N1 in poultry and wild birds (but not cattle or non-avian species) as a notifiable animal disease subject to regulations to control it and international reporting requirements. In the diverse dairy industry, where farm owners may operate independently of each other, control strategies based only on voluntary efforts to report and otherwise respond may not meet the need.

As a major step to centralize some control, the department ultimately opted to leverage 7 U.S.C. § 8305, a law that authorizes the agriculture secretary to prohibit or restrict animal movement in interstate commerce. This statute is long on the books—it became law in 2002—and a month-long hesitation to use it to intercept the spread of an alarming pathogen is troubling given that viruses have no such hesitation.

Although USDA's reticence undoubtedly relates to the fact that, unlike COVID, the information in question includes inherently business-sensitive information, but that does not negate the USDA's public health duty. This is particularly important at a time when trust in government institutions has waned, and the American public remains skeptical of government messages about novel infectious disease. The tensions between business sensitivity and public health can be balanced, as the department successfully does in its dealings with the poultry sector.

Even if this outbreak is contained, the prevention, detection, and response efforts needed are exactly the dress rehearsal the United States requires to be prepared to answer a future zoonotic global pandemic threat that emerges on its own soil.

The USDA must do its part but cannot on its own handle this large-scale event that cuts across diverse sectors. Federal regulators need to pick up the pace, expand the scope of active surveillance and response—and take this threat more seriously.