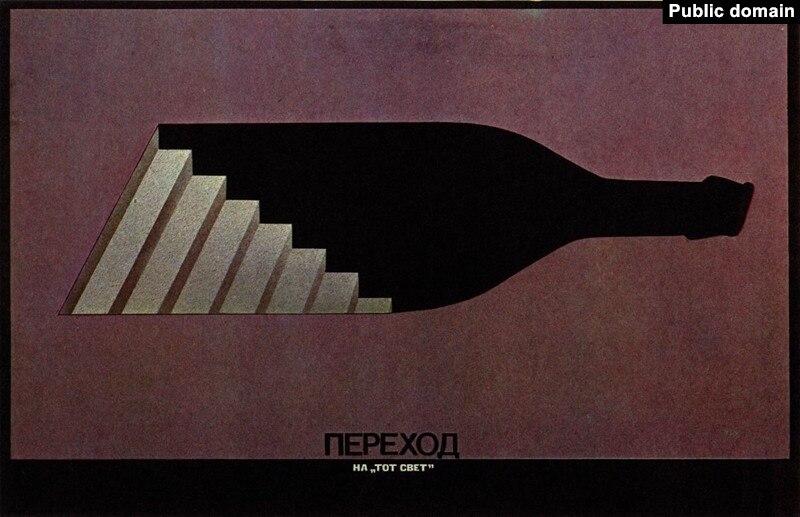

Alcohol-related deaths are rising across much of the world and although the World Health Organization has identified a number of evidence-based policies that countries can implement to curb excess drinking, few have adopted them.

One such bright spot is Lithuania. Spurred by a high burden of alcohol-related deaths and led by a crusading health minister, the country rapidly implemented a series of measures that have already cut mortality in the country.

Mindaugas Štelemėkas a professor at the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences and a specialist in alcohol policy, spoke with Think Global Health about a “natural experiment” that the country set in motion when it began to earnestly tackle the harms of excess drinking.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What’s Lithuania’s history with alcohol?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: As a post-Soviet country, Lithuania has a solid drinking tradition. Binge drinking is popular. People tend to seldom drink, but when they do drink, they drink. This is the most harmful drinking pattern we could have. It has a significant impact on our health indicators. Lithuanian men, who are the ones drinking the most, have a ten-year shorter life expectancy than women, one of the biggest gaps in the European Union.

Alcohol use is related to many health and mortality indicators and some of those indicators react very quickly to any policy changes. This is what makes alcohol unique. With tobacco control policies, we have difficulty assessing the impact because it takes so many years to observe. With alcohol, we can see the effects quite quickly.

A suspected drunk policeman hit children going back from school. Accidents really shake society.

In the mid-1980s, when Lithuania was still occupied by Soviet Union, a Gorbachev campaign against alcohol had some positive results on Lithuanian health indicators. When we regained our independence in 1990, that policy was basically eliminated and alcohol consumption was uncontrolled, so we really got into a bad situation. Then, around 1994 to 1996, new alcohol control policies were introduced and the country’s first alcohol control institution was established. When we were preparing to join the European Union before 2004, the trend was toward liberalization, so we allowed alcohol sales in petrol stations, people were drinking more, and road safety declined notably. People were driving drunk and several major accidents were especially significant. In one, a suspected drunk policeman hit and killed several children going home from school. Accidents like that really shake society.

So, in 2007, our parliament decided to intervene and declared 2008 “the year of sobriety.” NGOs became more active. A package of alcohol control policies was introduced. After many years without increases, lawmakers increased excise taxes on alcohol and introduced both limitations of alcohol advertising and some availability restrictions on sales of alcohol at night. Basically, good, evidence-based alcohol control policies. That was the year, 2008, we saw the first major breakthrough with our alcohol control policies. Mortality started to decline, especially for men.

Think Global Health: Were you personally aware of all this at the time?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: I was still a student and I was not participating in debates on health and policy issues. Around 2010, when I started my PhD, I changed my dissertation topic from one focused on pharmaco-economics to a more public health-oriented one. Aurelijus Veryga became my supervisor. By the time I completed my doctorate, he decided to go into politics and to make real change. He was elected as a member of Parliament in 2016 and his political party was the key player forming the new government. Its main agenda was health policies, especially on alcohol. Veryga became a health minister.

The new parliament started implementing tough policies on alcohol control that we scientists were advocating for. In 2017, without too much discussion, they doubled the excise tax for wine and beer. The industry didn’t have time to start lobbying against it. That was the biggest increase in years. The next year, in 2018, they nearly banned alcohol advertising altogether, including on the internet, television, and radio. They also reduced hours of sale again, especially on Sundays. The lawmakers went even further than I would have expected: they had enough political will to increase the legal drinking age from eighteen to twenty.

Think Global Health: Is it typical for public health scientists to become members of government?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: It’s not. Politics is about compromises, so it’s not that attractive to go into. We academics can provide the analysis and project results. We can see — clearly — that this was an amazing natural experiment, and in collaboration with Canadian researchers we got a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to analyze and present this case of Lithuania more widely.

Think Global Health: Why is Lithuania’s experience a good natural experiment?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: According to the World Health Organization, there are three “best” alcohol control policies that are inexpensive to implement and provide good results for all of society.

The first is alcohol taxes large enough to reduce the affordability of alcoholic beverages. Then comes availability, primarily reducing hours of sale, but also reducing the density of outlets that sell alcohol. The third is restrictions on alcohol marketing, the most difficult to analyze. It’s said that these marketing restrictions work most significantly for younger people, who are not yet drinking much and are still forming their attitudes toward alcohol. When you remove alcohol advertising, you basically remove the main way they develop positive attitudes about alcoholic beverages. People then tend to drink less and, in the future, fewer of those people start drinking.

Think Global Health: So implementing these in Lithuania was a major intervention?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: It happened in a two-year interval: 2017 when the excise tax was doubled, and 2018 when multiple measures were implemented.

From around 2014 to 2019, per capita alcohol consumption fell by 2.8 liters.

Think Global Health: What do we know so far about the results?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: The most significant and evident result was that the major increase in excise taxes pushed down all-cause mortality in Lithuania by 3 percent. That year—2018—when the policy was implemented, it may have saved more than a thousand lives. Alcohol-related mortality declined, as did other types of mortality. We are still analyzing the effect on hospitalizations; it’s more complicated to work with that type of data.

From around 2014 to 2019, per capita alcohol consumption fell by 2.8 liters—a really sudden reduction. The increase in excise tax revenues for the national budget was also significant. It was a win-win situation for the government. And, of course, the alcohol industry lost.

Think Global Health: Are you optimistic that these regulations and laws will be retained, or is it possible that opponents of the measures will reverse them?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: Over the last three years, we have managed to keep the current laws intact. I think this is a substantial achievement. We need to steadily increase excise taxes. For three years, the current government approved an increase — not a huge one but a steady one. Of course, it’s related not to their strong belief that it can significantly influence public health indicators, but more to the attitude to get extra income for the budget.

Think Global Health: Who has been the most important in keeping alcohol on the policymaking agenda?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: We have a nicely working alliance between the academics and NGOs. I’m also a part of Lithuanian Tobacco and Alcohol Control Coalition. We are always there when policies are debated on tobacco and alcohol-related questions. Quite often we can show the data that these policies do work, and the pool of data is increasing every year. I’m very happy for that.

Some members of Parliament are pro–public health. Aurelijus Veryga, former minister of health, is now a member of Parliament in the opposition, but he’s always active on this issue. He is, of course, not alone.

Think Global Health: Is there anything that Lithuania’s experience can help other countries achieve in terms of reducing deaths?

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: Our experience is that the policies do work and you can have an alcohol advertising ban because international companies respect national regulation.

To implement strong policies, you need to have strong political will. In the case of an alcohol advertising ban, media were claiming, “we will move away from Lithuania, we will register our companies outside Lithuania, we will still broadcast news for Lithuania but you will not get the taxes.” This turned out to be false.

The messages the alcohol industry uses in different countries tend to be quite similar from one country to another. I think that many experiences Lithuania had, especially the arguments that industry used, are very likely to be used in other countries as well. This, I think, is an important lesson from Lithuania.

Think Global Health: What do you think the next policy innovations would be?

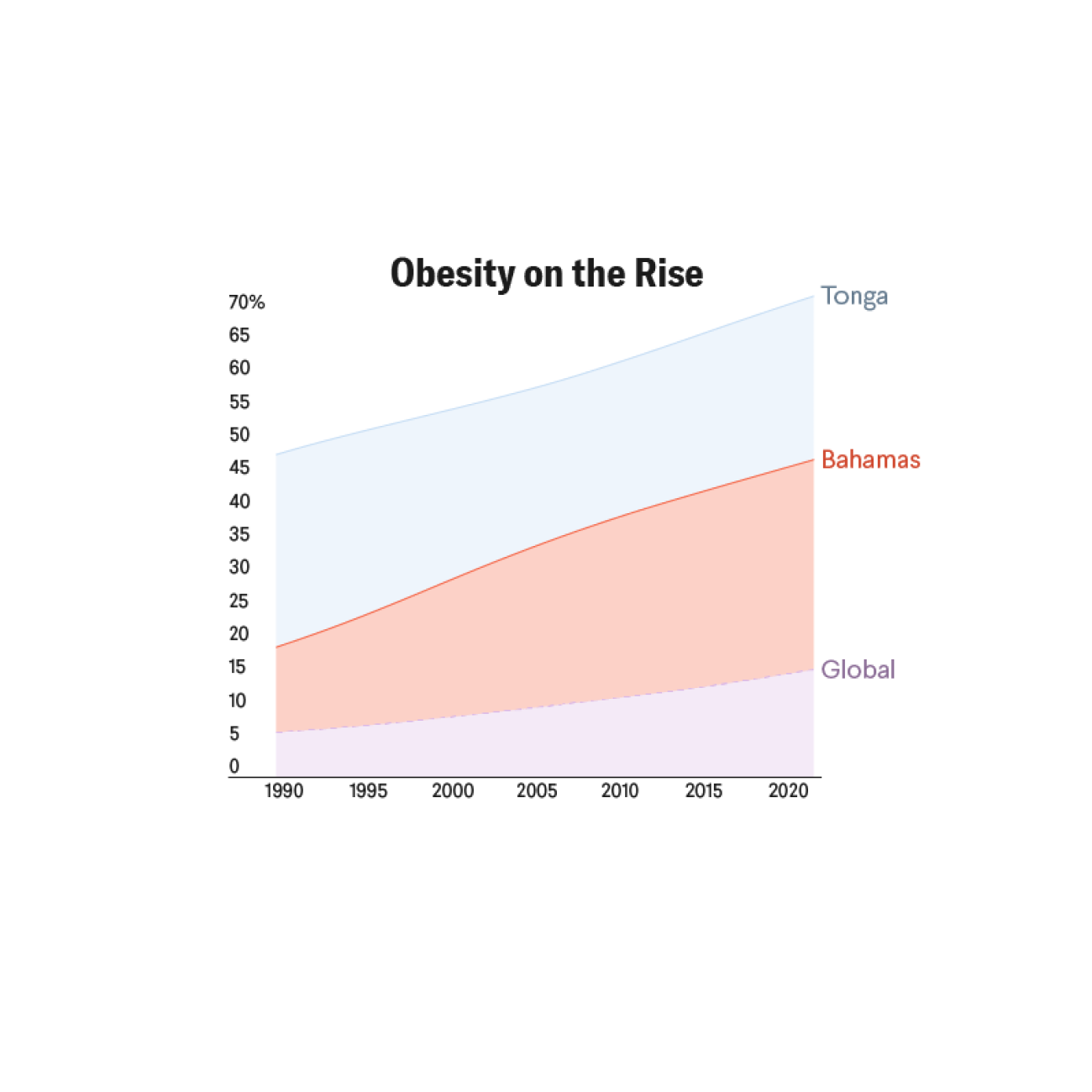

Mindaugas Štelemėkas: Debate is ongoing about the labeling of alcohol beverages. Non-alcoholic beverages have complete nutritional information but, for some reason, alcohol beverages do not. We recently discussed this matter with Latvian colleagues, who are currently having the policy debate themselves. People have the right to know the nutritional value of alcoholic beverages because alcohol generates a lot of empty calories and that is associated with extra weight gain.

This issue is important to the entire European Union, that complete labeling information for alcohol beverages is still not provided. Another issue, of course, is labeling with warnings that alcohol causes cancer, that alcohol should not be drunk by pregnant women, and so on. But those are questions for the future, or at least the near future.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity.