Nine months after the first formal notification of atypical pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China, and seven months since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, we’ve hit the tragic milestone of one million recorded deaths worldwide, with no end in sight.

Coronavirus cases in Africa are twenty times lower than the U.S. case rate

Most of Africa has yet to experience the explosive growth in cases and deaths seen in other countries. A big reason is likely because Africa’s political and public health leaders stepped up to meet the challenges of COVID-19, drawing from their experiences with past epidemics to mount an early and rapid response. So far there has been fewer than one confirmed case for every thousand people on the continent—more than twenty times lower than the U.S. case rate—and fewer than 25,000 reported deaths.

Why has Africa seemingly been spared the worst of COVID-19? It is possible the virus may simply not have hit there yet with force. Or perhaps we have seen a huge public health success story, and effective and broadly supported measures such as business and school closures and mask-wearing mandates have limited the impact. Or maybe the disease is silently present—it may have hit, but the death rate was much lower because of Africa’s much younger age structure and the fact that not all coronavirus deaths were confirmed.

People throughout the continent remain at risk

Africa is diverse, and all of these factors may be relevant in different countries. But as we learn more about why Africa’s burden has been lower, we must recognize that people throughout the continent remain at risk. The pandemic is far from over, and countries need to continue containing COVID-19 while minimizing burdens on the population. Personal protective measures such as the 3 W’s—wearing a mask, watching distance, and washing hands—are low cost, aren’t economically disruptive, have high acceptance and high impact, can be easily followed by the public, and present one of the best opportunities to limit disease spread.

The Threat of Health-Care Disruption

Evidence from past epidemics and initial reports from COVID-19 suggest that the greatest threat of COVID-19 in Africa will be indirect—arising from disruptions in health-care delivery and not from the disease itself. During the West Africa Ebola epidemic, more people died from a lack of regular medical care, particularly treatment for malaria, than were killed by Ebola.

COVID-19 may reverse many of the gains and progress we have seen

In Africa so many health services are vitally important to preserve life, and because people there are so young on average, deaths from health-care disruptions due to COVID-19 are almost certain to outnumber deaths from coronavirus infection again. Of particular concern are delays, disruptions, or other departures from routine care, which will cause additional illness and death from the three M’s—malaria, measles, and maternal mortality—as well as from other diseases, including HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis. Unfortunately, there are indications that the COVID-19 pandemic may reverse many of the gains and progress we have seen in combatting these illnesses.

We can limit these deaths by protecting health-care workers, strengthening health systems, and maintaining essential health services. My group (T.F.), Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative of Vital Strategies, has joined with WHO and the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as well as major nongovernmental organizations, including the World Economic Forum, in a public-private Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19 (PERC) to reduce the pandemic’s impact in Africa. This partnership recently released a status report showing how the pandemic continues to affect communities, including disrupting essential health services.

Hesitant to seek care due to actual or perceived risk or inability to pay

The PERC report supports the troubling concern that the COVID-19 control measures quickly implemented by many African Union (AU) member states are now causing secondary impacts that will be far greater than the disease itself. Many communities across Africa report difficulties accessing critical health services due to the extra burden placed on health systems, interruptions to medical supply chains, and restrictions on movement. People have also been hesitant to seek care due to actual or perceived risk of transmission in clinical settings or their inability to pay for care—a burden that has increased due to the adverse economic impacts of the pandemic.

What the Report Found

Cameroon was heavily affected early in the pandemic but has since sharply reduced disease transmission. But the pandemic control measures disrupted immunizations for children at risk of infection from measles, seasonal cholera outbreaks, and other dangerous diseases. Nearly half of people seeking medications in the country reported difficulty obtaining them, and eight out of ten regions in Cameroon are experiencing measles epidemics.

Eight out of ten regions in Cameroon are experiencing measles epidemics

In Tunisia, where cases are currently increasing rapidly, the vast majority of people report difficulty accessing health care or needed medication. The most common delayed or skipped medical visits were for routine check-ups and treatment of noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Disruptions in care for managing these conditions could be deadly. All countries surveyed for the PERC report saw significant and potentially life-threating impacts of the pandemic on their health services.

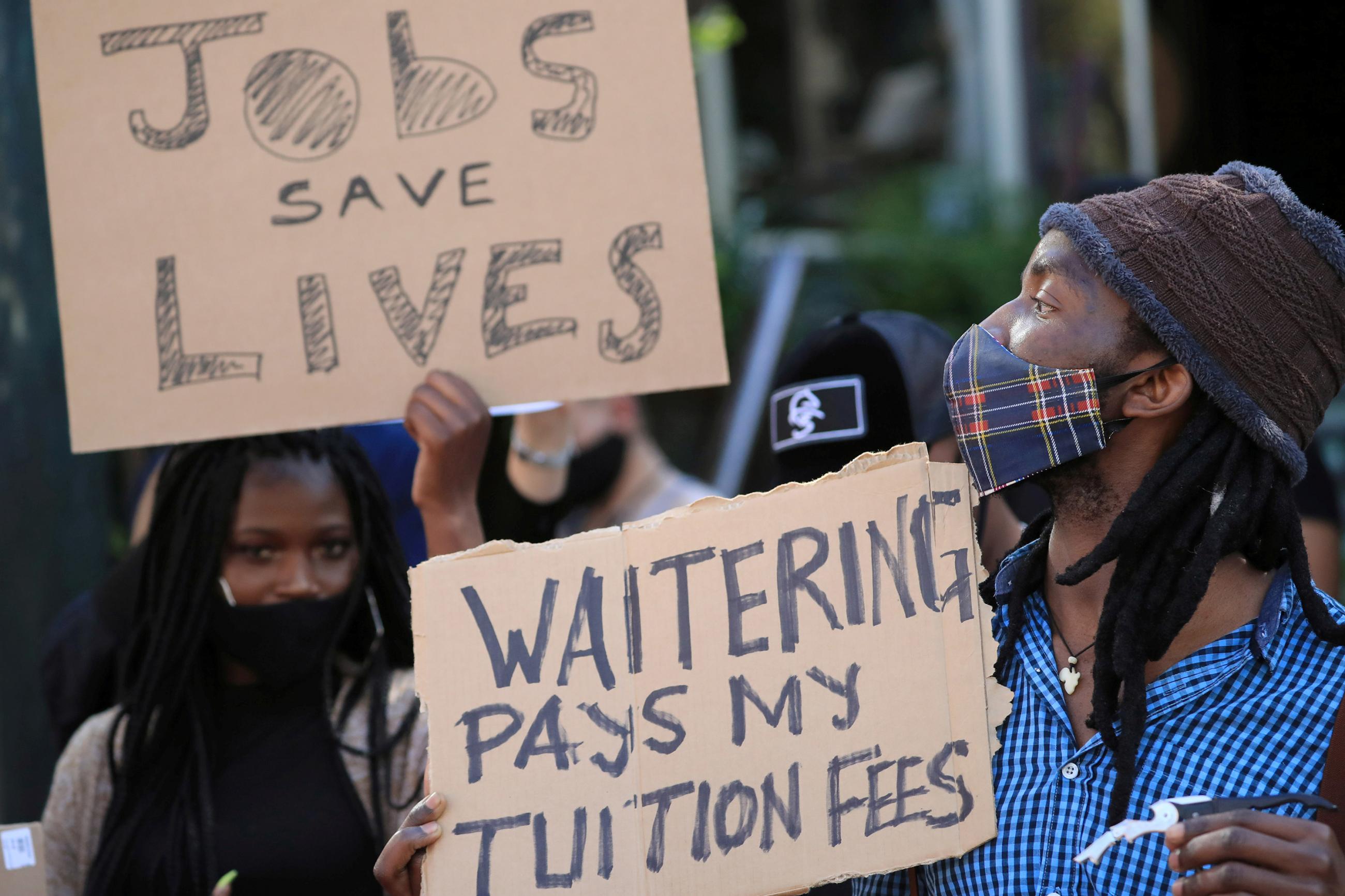

In addition to missed or delayed health care services, seven of ten survey respondents reported that their household income had declined from the previous year, with the same proportion reporting difficulty accessing enough food to eat. COVID-19 will cause the first increase in global poverty in more than two decades, plunging millions back into poverty. Declines in socioeconomic status result in poorer health and increased deaths.

COVID-19 will cause the first increase in global poverty in more than two decades, plunging millions back into poverty

Controlling COVID-19 is the only way to safely reopen the economy. Based on analysis of survey data, the Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19 coalition recommends important strategies for African Union member states to find a balance between saving lives and saving livelihoods as they respond to the pandemic. Improved data collection and analysis to better support decision-making is critical to finding that balance. The true cause of low numbers of COVID-19 related deaths in Africa is obscured by missing data and inconsistencies. Governments must improve testing rates and data collection on a range of indicators, including excess mortality and access to treatment of key health conditions. Only then can a clear picture of the impact of COVID-19 and the measures taken to combat it be compared with the significant secondary consequences to health systems.

Governments and international aid partners must do more to maintain essential health services, and in particular better protect health workers. They need improved training on infection prevention and control, including availability of personal protective equipment, as well as increased access to testing and, if infected, medical, financial, and social support. Better protection for health workers means better protection for patients and for the community.

Community engagement, food security, and economic recovery

Governments must also encourage people to seek needed care through effective risk communication and community engagement. This includes countering dangerous misinformation about COVID-19 and what works to prevent disease spread. Governments should also take steps to increase food security and economic recovery through cash transfers or direct food support, leveraging existing social insurance and social protection systems.

The trajectory of the pandemic across Africa, and indeed much of the world, remains uncertain. We can expect that, even with a safe, effective, and accessible vaccine, COVID-19 will be with us for the foreseeable future. The more countries take the same data-driven approach adopted by African Union members to confront the pandemic, the healthier the world will be to weather the pandemic and prepare for inevitable future health threats.