Last week, China announced it will reduce the number of abortions performed for "non-medically necessary purposes," a move that may signal the government’s concern over shrinking birth rates. Think Global Health asked Leta Hong Fincher, an award-winning journalist and author of "Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China," for her thoughts on the policy change. Hong Fincher is also an adjunct assistant professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Columbia University.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What is your take on the recent news that the Chinese government plans to pull back on abortions for "non-medical purposes"?

Leta Hong Fincher: For several years, I've expected that the Chinese government would be moving in this direction and would begin to restrict abortions, which would be a huge change in policy for China. For well over 30 years, they have actually used abortion as an integral part of their population planning. And in many cases, especially in the early years following the one-child policy, particularly in the 1980s, they forced a lot of women to have abortions. Even today, we see some reports of forced abortions among Uyghur women in Xinjiang. Abortion has been very widely used.

Think Global Health: So, the roots of this change go back pretty far?

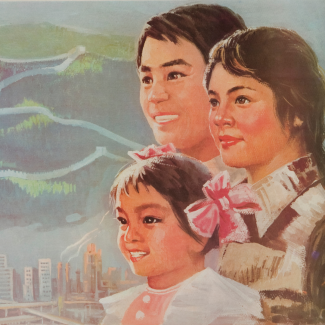

Leta Hong Fincher: The Chinese government has had a so-called one-child policy for over three decades and then at the end of 2015, it announced it was adopting a so-called two-child policy and along with that change the propaganda was very aggressively focusing on especially educated women, trying to get them to have two children instead of one. For well over a decade, the government has been trying to push educated Han Chinese women into marrying and having more children, trying to push them into very traditional roles of wife and mother in the home.

In my first book, "Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China," I looked at government propaganda and its use of the term "leftover women" to stigmatize single women in their mid-twenties and early thirties, to push them into getting married. Pushing them into getting married was the first step and then the next step was to push them into having more children. It's a little bit complex, but it's part of the government's effort to engineer a so-called "higher quality" population.

"There has been this massive crackdown on feminist activism—it's been happening since the jailing of five feminist activists in 2015"

Think Global Health: Have these policies achieved the end results that the government is hoping for?

Leta Hong Fincher: We can see from the statistics on birth rates that the change from a one-child to a two-child policy really didn't have an impact. It had a little bit of a boost in births for one year, but since then, the birth rate has still been falling. We just saw the Chinese government introduce an official three-child policy just a few months ago.

Think Global Health: You've written extensively on the feminist movement in China. Can you provide some context in that area?

Leta Hong Fincher: There has been this massive crackdown on feminist activism—it's been happening since the jailing of five feminist activists in 2015. It's in that context that this new line about abortions for non-medical purposes being reduced is being inserted into the State Council document on women's rights.

I've noticed that a lot of people on social media are saying don’t freak out, it’s only one line in an incredibly long document and we don’t need to overreact. So, I will admit that we don't know what we’re going to see on the ground. It all depends on what happens and how this change in emphasis, in rhetoric, will be enforced by different institutions, the population planning cadres, the people who do the outreach—from the big cities all the way down to the smallest villages in China. These are the people who carried out the very coercive elements of population planning in the past, checking to see if a woman was pregnant, if she had violated her quota of children, sometimes forcing abortions, forcing insertions of IUDs. It has been historically an incredibly abusive practice.

So we don't know yet what is going to happen. But this is another step in a continuum. And the direction of that continuum has been very clear since 2007: to try to get educated Han Chinese women to marry and have more children.

Think Global Health: How might this affect Uyghur women?

Leta Hong Fincher: In the case of Uyghur women in Xinjiang, they are seen by the Chinese government as troublemakers, and as "low-quality" potential "terrorists." Because those women are seen as undesirable—Uyghur and Kazakh women—the government will want to see the birth rates among those women driven down. It's a practice of eugenics—it's very clearly eugenics.

Think Global Health: The government is calling on men to "share responsibility" when it comes to preventing unwanted pregnancies. Any thoughts about that line and China's perspective on gender equality?

Leta Hong Fincher: These government proclamations or policy declarations or speeches, anything official coming from the Chinese government is going to contain rhetoric that states that the government supports gender equality. Gender equality is an essential part of Communist Party principles. Support for gender equality was written into the constitution of the People's Republic of China. The early history of the Chinese Communist Party has been in many ways pro women's rights. There was very strong rhetoric of gender equality leading up to the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949. And of course, Mao Zedong, who was the preeminent leader after the revolution, his most famous saying ever was, "women hold up half the sky."

"The feminist movement in China is very resilient, it's very deep, it's very broad"

Today, you still see the legacy of that historical support for gender equality. But in this particular document, where it says that men need to take responsibility, I don't really put a lot of weight into these kinds of suggestions because they don’t really indicate a major policy change. It’s just rhetoric. Looking at rhetoric coming from the Chinese state media, there has actually been a lot less rhetoric declaring the Communist party support for gender equality over the last 15 to 20 years compared to the past.

Everything that I have observed in my research and extensive interviews, which I started doing 11 years ago, indicates a really clear emphasis on patriarchal control of society. In my second book "Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China," I write about patriarchal authoritarianism in China. The Communist Party today is nothing like the Communist Party of the 1950s and 60s, and even the 1970s and 80s for that matter. There's been a huge resurgence of gender inequality of many different kinds. For example, there has been a real decrease in women's labor force participation. There’s been a huge, increasing gender gap in income.

One thing that was positive is that in 2016, China adopted an anti-domestic violence law. It was a real legal milestone. However, in subsequent years, it's pretty clear that that law hasn't been enforced. There are so many examples of this in contemporary China where you see that the language of the law looks pretty good on paper, but it's simply not enforced. And not only is it not enforced, it’s actually abused.

Think Global Health: It sounds like women's rights, including women's reproductive rights, are on shaky ground.

Leta Hong Fincher: I don't see any indication that the central government is trying in any real way to support women's rights. I see the complete opposite: arresting young feminist activists for doing nothing wrong, and in recent months seeing another huge crackdown on feminist content on social media in China with individual feminist accounts being deleted and a lot of censorship of feminist content.

Think Global Health: You're saying these policy documents seem like empty rhetoric?

Leta Hong Fincher: Let me be clear that whenever the rhetoric coming from the Chinese government appears to be supportive of gender equality, I have to say I'm extremely cynical. I'm not saying I don't believe anything put out by the government. But in recent years, with the massive crackdown on women's rights, on feminist activism, the anti-domestic violence law that hasn’t been enforced, and the population planning policies that have dramatically changed—I think we need to take this statement about the need to reduce abortion more seriously. Times are different.

"The role of NGOs and non-governmental organizations has been severely reduced over the last decade"

Think Global Health: Where does this new policy leave the health-care providers? Is there an equivalent of Planned Parenthood in China?

Leta Hong Fincher: There's no Planned Parenthood type of organization in China. The role of NGOs and non-governmental organizations has been severely reduced over the last decade. And this crackdown on feminism has shut down formerly, already beleaguered, very small women's rights organizations. What you do have is the All China Women's Federation. It's not officially a government agency but effectively it is. I've written about how the All China Women's Federation is very reactionary. It serves to control women as opposed to protecting women's rights.

There are of course really great doctors in China. I'm not in China right now so I'm not able to tell you what’s happening with women seeking abortions. What I do see potentially happening is that the hospitals or any physician practices—which are all overseen by the Communist Party, which has Communist cells in virtually all major businesses in China—may become more limited in their practices. It could very well become more difficult for some people to get abortions in China.

Think Global Health: What do you think the future of women's reproductive rights in China looks like?

Leta Hong Fincher: The feminist movement in China is very resilient, it's very deep, it's very broad. And it is posing an incredibly complicated challenge to China's government. It is the most resilient, the most dynamic social movement that China has had since 1989 and the pro-democracy uprising that ended up being crushed in the Tiananmen Square massacre. Whatever hope I have about the government not restricting abortion is because of the strength of the feminist movement. Because women overall in China—particularly young college-educated women, and even girls who are in high school—have gotten involved in feminist activities. The country has changed from the ground up. There's this grassroots rights consciousness among young women and the LGBTQ community, as well.

It is very possible that the central government is not going to enforce or declare any further restrictions on abortion. It may just leave it at that one line and maybe we won't see any concerted move to restrict access to abortion. But that would only be because Communist Party officials realize they're doing this delicate dance here. It's complicated for them. If they announce some draconian ban on abortion, the outcry across the entire country would be enormous. And does Beijing really want that? I doubt it. And that is why I am still somewhat hopeful. But my hope does not lie with the Chinese Communist Party and their policies. It lies with people on the ground who are pushing back against all of these new forms of interference in the reproductive lives of all people in China.